Ben Fishel • • 14 min read

The Secret Religion of the Dollar: How Money is Really Impacting Your Life

“Yes, one can take a whole hand full of crisp dollar bills and practically water your mouth over them, but this is a kind of a person who is confused – like a Pavlov dog who salivates on the wrong bell.”Many of us feel conflicted by money. We are uncomfortable with the control it has over our lives, but we know we are stuck in a system in which we need it for survival. We see it cause wars, but also seemingly heal the sick. It’s something we touch every day but never seem to really grasp.

— Alan Watts

Did Money Replace God?

“The number one reason people hate America, the number one reason is because of our religion. Americans worship money, we worship money. Separate God from school, separate God from work, separate God from government but on your money it says in God we trust. All my life I’ve been looking for God and he’s right in my pocket! Americans worship money, and we all go to the same church, the church of ATM.”

— Chris Rock, Never Scared

The 20th century saw the fall of widespread religious influence like we have never seen before.

At home, many people still practiced their beliefs, but the dominant cultural narrative was one that lacked a firm confidence in god, and in turn a cohesive philosophy. The notion of divinity for example, no longer held a position of paramount importance in our lives, as it had done for millennia. Millions of individuals in the Western world seemed to keep their religious affiliations for cultural rather than spiritual reasons.

But ideologically this wasn’t enough; it left a profound gap in our culture. Man has always needed a story, a myth by which to arrange his belief systems in a way that his psyche can digest. The narrative that took the place of traditional Judeo-Christian values in Western culture was fundamentally based upon the ideals that came with capitalism. One key underlying belief was that men were in control of their own destiny and should build, produce, and own the fruits of their individual labor.

Read this: 10 Reasons You Should Never Get a Job

The cause of this change is debated but largely attributed to the scientific revolution and the emergence of free markets, neither of which wanted to be shackled by theology. In the United States, the American Dream — the pursuit of happiness — was intrinsically tied to these notions. The dream was initially a modest ideal: basic freedoms and the potential for financial stability. Though what has spawned in the last half a century is a culture obsessed with consumption, and one that expects nothing less than extravagance.Cultural Misconceptions About Money

“Though the monoculture naturally embodies issues surrounding money, the economic story represents a much more nuanced and insidious tapestry of beliefs and assumptions that fall into three categories: who you are as a human being, what the world is like, and how you and the world interact.”Our current model of capitalism mirrors organized religion in that it is hierarchical in its dispersion of truth. Confusion is rampant as the markets move on speculation and the bankers adopt the role of priests. Amongst the laymen, economic illiteracy is widespread. It is unsurprising then that wealth should therefore be so concentrated in so few hands. To delve deeply into the true nature of economics, banking, world trade, and financial markets, would be far out of the reach of this article, but I will touch base on a few important cultural misconceptions many of us share.

— Michael F.S., Monoculture: How One Story is Changing Everything

The accumulation of money is the end goal.

Do you find yourself getting over-excited as the number in your bank account goes up, or depressed when that number goes down — even when you’ve put it to good use? Or even when you aren’t looking to buy something or don’t necessarily need the money at this moment in time? This is the result of an ethos which places the accumulation of money as the end goal, as opposed to seeing it for what it is: a tool to get what you truly want, usually a particular experience.-

The value of money is always fixed.

The word currency is derived from Middle English, curraunt, which means ‘in circulation.’ Think current. The value of money both in relation to the market, and in relation to our personal situation, should be thought of as flexible, transient — like water. $1000 means something different to us depending on how the market is performing and whether we need it to support our living situation. But we no longer see that: we attribute rigid, unchanging physical properties to currency, which only serve to deepen our disconnection from its true, malleable nature. Money is just the exchange of productive energy between two individuals or organizations. The value that we give to whatever is exchanged is constantly changing. We should allow money to come in and out of our lives with as little attachment as we have to the air we breathe. When we lose sight of this — and attach a divine quality to money — we form an anxious attachment to the amount of money in our wallets or bank accounts and we are more easily manipulated by marketing and materialism.

-

Money is the root of all evil.

Money is not the root of all evil. It is simply a way to facilitate exchange. It is the overbearing ethos of scarcity — driven by individualism and a belief that others won’t catch us if we fall — that causes mankind to do horrible things. It is this fear, this feeling, that causes us — even when we have more luxury than 99.9% of people throughout human history — to still feel so close to having nothing. The result is a culture that allows one half of the world to wrestle with obesity while the other half starves.

-

More money = more choice = more happiness.

The economic narrative tells us that money gives you freedom of choice and freedom of choice is ALWAYS better. As a consumer you are most free when you can purchase whatever you want. However, although we’re equipped to deal with choice and have developed adequate decision-making faculties, we’re far from able to handle the degree of choice we have in the modern world. Hence the aptly named psychological phenomenon ‘analysis paralysis,’ which could be a contributor to the abnormally high rates of depression we are seeing in young people. More money may give you more freedom, but it is unlikely that this is conducive to more happiness after a certain point.

-

Money cannot buy happiness.

Although I just argued that more money does not necessarily equal more happiness, I’ll admit that it can help, in some cases. I don’t like the cliché, “money cannot buy happiness,” because it oversimplifies both the idea of money and the idea of happiness — it promotes black-and-white thinking. It is a generalization. I like to think of happiness as the product of three things: will, wisdom, and circumstance. I think you can be happy with only one or two of these, but lacking in one of these areas may prevent you from being so.

For example, you may have read all the books on happiness, and you may have the willpower to act in a way that is conducive to you becoming a happy person — but you may be in grim circumstances that won’t allow you to be so. Likewise, you may be in the right circumstances and have all the wisdom you need, but don’t have the willpower to break habits that may be stopping you from being happy. The role of money in the equation is only significant insofar as it can help you better one of the three criteria — if you don’t have the money to buy books or get an education, it can be difficult to gain the opportunities for you to do what makes you truly happy. Similarly, money can change some elements of your circumstance, like if you have serious medical issues. And in the case of willpower, our daily supply is limited, and money can alleviate circumstances that may inhibit the will to focus on your happiness.

Does Money Really Make the World Go Round?

The impact that the economic narrative has had on our culture runs so deep that it afflicts literally every area of our lives. Everything from our political policies down to our sense of identity, the depth of our relationships, our health, and the place of art and creativity in our existence is practically molded by an economic narrative. This narrative is essentially a series of interweaving ideas, attitudes, and behaviors that are dictated within the framework of capitalism. A lot to take in, I know, so it’s best I give a few concrete examples. This list is by no means extensive, nor is it in any way in order — it is simply some ideas that have stuck out in my mind.The Myth of Individualism

“Americans cling to the myth of individualism as though it were the only normal way to live, unaware that it was unknown in the Middle Ages (except for hermits) and would have been considered psychotic in classic Greece.”Individualism as an ideology is purported to have arisen in part from the solitary nature of the early days of America — think the lone ranger in the Wild West. But it is capitalism and the hypercompetitive nature of money-grabbing that have further entrenched our divided culture. The result has been the rise of transactional relationships: at home, at work, and in our communities.

— Rollo May, The Cry for Myth

Self-Defined One-Dimensional Identities

A society in which individuals largely identify with their earning potential is inevitably going to be one where a large percentage of people will have to self-identify with failure. As children grow up, we constantly tell them they are special. “Mary is such a talented drawer.” “John is an exceptional footballer.” “Brian is a natural mathematician.” But what happens when Mary, John, and Brian get to their mid-20s or early 30s? Mary stops drawing because she has to focus on her career. John isn’t good enough to go pro, and his bank job gets him little praise for the years he spent honing his craft. Meanwhile, Brian crunches numbers for a mid-size accounting firm, but doesn’t feel challenged. When earnings are how you measure your success, there is a very small percentage of people — those who are the wealthiest in their social circles — who will identify as successful. This can be dehumanizing for the many of us who don’t fit into that category. A black and white view of the world, when picking yourself up after a failure, doesn’t allow you the room to say: “I didn’t make much money this year, but I wrote the novel I always wanted to, and I’m okay with that.”Narrow Fields of Knowledge

It’s a painful irony that our philosophical and spiritual ideals have evolved very little over the last 2000 years. Now before you argue about ‘Murica, free speech, democracy etc., I want to point out that a lot of these ideas were prevalent as far back as ancient Greece. Meanwhile, fields directly associated with wealth creation have made unimaginable leaps and bounds. This isn’t to undermine the great scientific or technological discoveries of the last century, but our obsession with the consumption of consumer goods can seem pointless in the face of many real issues.Capitalism has preserved the idea that our progress as a human race is linear — that civilization ALWAYS goes forward. We can hardly imagine that our youth may be less intelligent than the youth of a hundred years ago, especially if standardized testing results have improved — but if we look outside narrow IQ-based definitions, towards emotional intelligence, spiritual intelligence, resilience, or basic survival intelligence, we may be falling far behind.Worshipping False Idols

Associating money with the sacred lets us believe that there is some magic to its accumulation. As a result we are all pagans — worshipping false idols in the guise of millionaires and Kardashians. Becoming rich isn’t like gaining enlightenment or becoming a world-leading theoretical physicist or a master of martial arts. Chance and circumstance come into play a lot of the time, and we end up following the entertainers rather than the educators. And though many entertainers can have a lot to teach us, it is often those who are the most commoditizable — who elicit shock value or perpetuate drama — that we are exposed to.Devaluation of Man’s Creative Nature

Capitalism has resulted in a devaluation of art and creativity. Artistic success is defined by how well one performs in the market — how much a painting goes for at auction, how many records are sold the first week, or if you can sell out Madison Square Garden. This completely undermines the purpose of art, encourages trend-chasing, and stifles originality.The Revaluation of the Environment

Money doesn’t destroy all values; it simply changes them. Whereas early religions, such as animist cultures, valued the earth above all else, capitalist cultures value endless consumption more than the environment. The CEO of a logging firm for example, isn’t against the environment; he has simply been conditioned to believe that its preservation is less important than financial gain. Our natural world is now supposed to be valuable because it is profitable, not because it is priceless.But isn’t this all normal? Isn’t capitalism just an expression of our selfish nature?

One argument you often hear in favor of ruthless capitalism is: but isn’t mankind inherently selfish?The reality is that there are very few things you can say are ‘inherent’ to human nature. Man is not a fixed construct. We talk a lot about human nature, but if you were to derive any conclusions from how we live or behave now, you would see that what we are is akin to a lion on a tricycle performing in a circus; our environment is largely manufactured, our movement stunted, and most of our actions pointless from an evolutionary perspective. The reality is that different societies have acted differently throughout human history. There have been societies based on domination, and others based on partnership, societies based on individualism, and others based on cooperation.Read this: Do You Give Money To Strangers? The Answer Might Surprise You

The oversimplified version of history is this: men have always and will always be greedy. But this isn’t necessarily true. The bias in play is that when you read about history, you usually only hear of the conquerors, not the billions upon billions of people who lived tranquil and cooperative lives.We consider science and big business to be in each others’ pockets now, but this is hardly a new phenomenon. In fact, some historians believe that some of the specifics of Darwin’s theory of evolution were actually financially backed for strategic reasons. A much lesser-known early advocate for the theory of evolution, Alfred Russel Wallace, talked of the role of cooperation and peaceful adaptation in nature, which on a cultural level was entirely opposed to the beliefs needed for maintenance of the British Imperial system. Without going too far off track, you can see where I’m going — the supposed primacy of competitiveness in human nature, as compared to cooperation, isn’t necessarily clear-cut. Neither is the role of nature, nurture, epigenetics, or countless other cultural phenomena.There are plenty of loud moral absolutists on the far right and far left. The far right believe we need to stick with the current model of capitalism that we have, that we deserve all the fruits of our labor, and that any commitment to a wider cause is some form of professional slavery. This position is often founded on the Just World fallacy — i.e. the assumption that if you are poor, it is because you deserve to be poor. They completely underestimate the impact of race, social status, etc. on one’s ability to thrive in a capitalist system.On the far left you have people who believe we should move to some form of communism, socialism, anarchy, large-scale tribalism, or a series of self-sustaining communes, but at this point, in such a complex, interdependent and globalized world, it’s just not realistic to expect any of these to eventuate. To a large extent these views also fail to recognize that capitalism in general, despite its flaws, has been one of the greatest, if not the greatest, creative tool(s) for social cooperation in the history of mankind. This cooperation arises because capitalism is competitive, and in order to defeat your competition, you need to have a strong team or community behind you. As teams and communities strengthen, markets develop, and we look further and wider for new resources and innovation. The result, as we have seen over the last century, has been the opening of the global floodgates to allow for codependent businesses to trade capital. Whether we act altruistically with this cooperation is a matter of collective will. The great wars of the 20th century caused societies to work together to neutralize an immediate threat. The only problem is, we don’t recognize the threats posed to our personal and societal well-being, by the current model of capitalism, as immediate.So how can you make a difference in all of this?

What you need to do is first recognize that the religion of the dollar is most definitely a real threat to your own well-being. It’s a threat to your intelligence, your creativity, your self-esteem, and your relationships.When you see that, you can begin to accept some responsibility on an individual level for being a cog in a wider economic system. This means understanding that even though you live in a society that worships money, you have a choice to act in a way that is independent of that framework.It is only by constantly questioning the status quo and reassessing your values that you can release your attachment to money. The religion of the dollar will be pulled apart at the seams if we can come to realise that 1. It is a myth, and 2. We needn’t be reliant on that myth for our wellbeing. This article has tried to explain the truth behind the first point, and it is up to you to address the second. But stepping free is not as simple as consuming mindlessly, and maybe once in awhile over a couple of drinks saying to your friends “Oh well, I know this material stuff’s not really important.” It’s a matter of being conscious at all times of what you’re buying physically, and what you’re buying into ideologically, when you make a purchase. The resurgence of both stoicism and minimalism in recent years is an obvious backlash to the barrage of hedonistic consumption in mainstream culture. Proponents of these movements suggest that we ought to practice the art of frugal living from time to time. By spending intermittent periods living with little, your mind will be opened up to the idea that you can actually be happier with a lot less stuff.“Be moderate in order to taste the joys of life in abundance.”The question is not whether capitalism is inherently bad or — to revisit an old cliche — whether money is the root of all evil.The question is what will happen to our culture if it follows the path of least resistance — if it gives in blindly to the religion of the dollar?What will happen if we only buy into ideas, education, art, science, relationships that are profitable? The answer is an imbalanced society — a sick society — because illness comes as a result of things getting out of balance. The logical conclusion of a society driven solely by consumption isn’t going to be pretty; it’s going to be Orwellian.I don’t know if a system that eclipses this one will come along in my lifetime. Probably not. But if we start with ourselves, we can certainly lay the seeds for a more sustainable, prosperous, and egalitarian society for future generations.

— Epicurus

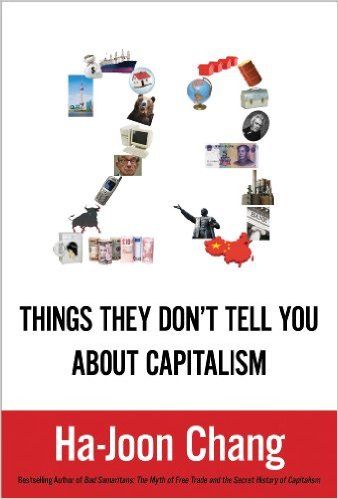

Recommended Reading — 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism by Ha-Joon Chang

If you appreciated this post, we recommend 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism by Ha-Joon Chang. This book is an accessible introduction to general economic theory. And in particular, it provides a straightforward look at a number of the challenges surrounding the institution of global capitalism in the 21st century. The author takes the view that although capitalism is the most effective economic system we’ve devised, significant government regulation is necessary for the creation of a just society. You can also read the key insights from this book in 15 minutes on Blinkist.

Further Study

Monoculture: How One Story Is Changing Everything — F.S Michaels

Sacred Economics: Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition — Charles Einstein

Capital in the Twenty-First Century — Thomas Piketty

![Seneca’s Groundless Fears: 11 Stoic Principles for Overcoming Panic [Video]](/content/images/size/w600/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/seneca.png)