Hans • • 11 min read

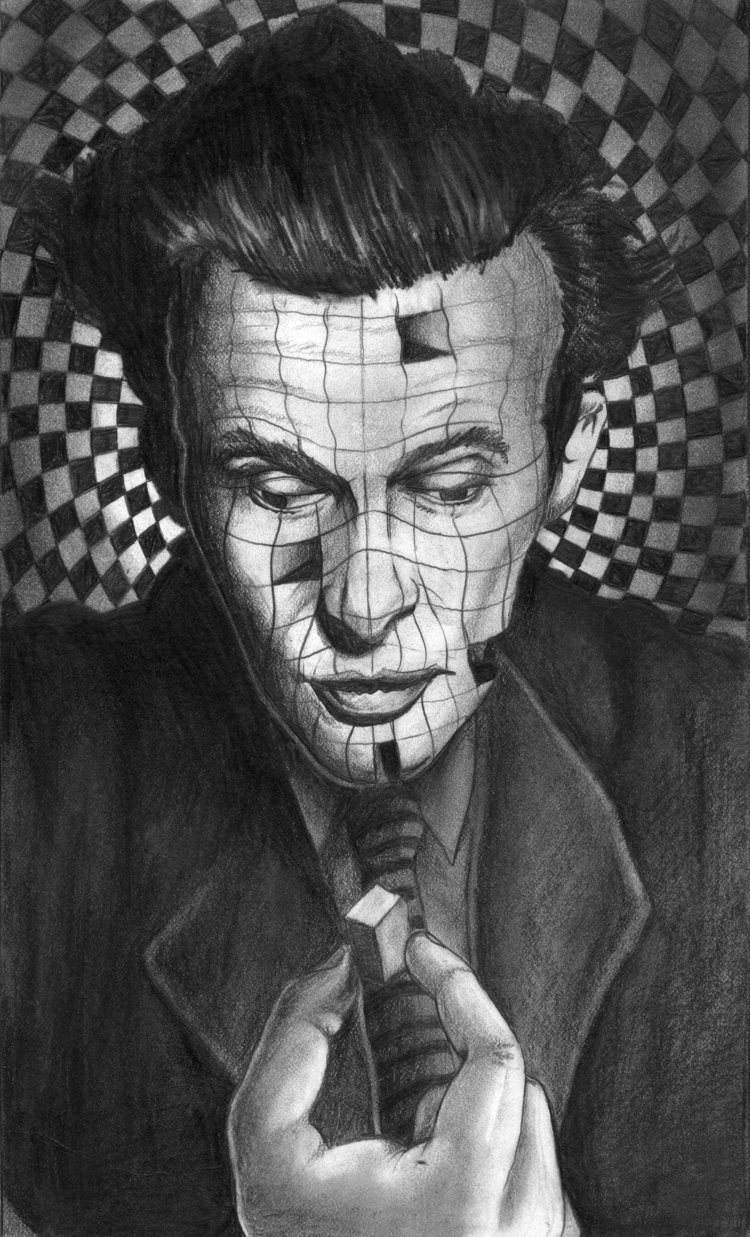

Terence McKenna, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and the Archaic Revival of Empathy

“Western civilization is a loaded gun pointed at the head of this planet,” Terence McKenna cautioned.

The 20th century psychedelic-visionary-scientist was right on point.

It’s a sad commonplace to assert the ubiquitous superficiality, alienation, stress, addiction, fear, trauma, depression, insecurity, and abuse that plague the West.

A little less clear is why we are so lost. How are we lost? And how did we get lost?

The answer is painfully obvious: we detached ourselves.

And I’ll say it right off the bat: the way back to ourselves is going to have to be through revisiting our embodiment, because that’s where the separation happens.

Understanding why this is so… that’s the tricky part. And this trickiness in itself already holds a clue.

How We Got Here

It’s tricky for our minds to switch to the mode of our bodies because we all have been culturally conditioned, for centuries, to mistrust our physical impulses.

The western “Era of Enlightenment” spawned the idea that humanity’s progress was to be made primarily by “Reason”. This meant logic and rationality, with a clear mind, untainted by the bodily passions.

Since then, the rational project of Western humanity has massively progressed. The ongoing development of our cultural self-image is culminating in the greatest dream that Reason could ever dream: Artificial Intelligence. At the horizon of our imaginations, we now visualize a disembodied God, an unemotional and unlimited machine of the Mind, that sees reality in infinite resolution, and that’s unbound by the fog of human feelings.

Welcome to the utopia of a logical society.

But Nietzsche amply warned us: a god who cannot dance should not be trusted. And the disembodied dream stems from a particularly perilous thought (which I’ll get to in a bit).

Granted, the danger of rejecting the importance of our bodies is no new insight, and neither is the suggested path for averting it. Have a read of something else McKenna said:

“We have gone sick by following a path of untrammeled rationalism, male dominance, attention to the visible surface of things, practicality, bottom-line-ism. We have gone very, very sick. And the body politic, like any body, when it feels itself to be sick, it begins to produce antibodies, or strategies for overcoming the condition of dis-ease. And the 20th century is an enormous effort at self-healing. Phenomena as diverse as surrealism, body piercing, psychedelic drug use, sexual permissiveness, jazz, experimental dance, rave culture, tattooing… the list is endless. What do all these things have in common? They represent various styles of rejection of linear values. […] I applaud all of this; because it’s an impulse to return to what is felt by the body—what is authentic, what is archaic—and when you tease apart these archaic impulses, at the very center of all these impulses is the desire to return to a world of magical empowerment of feeling.”

Re-inhabiting our bodies with authenticity is one of the most salient healing paths for us as individuals, as a species, and as a culture. But McKenna’s statement begs the question:

Why are our bodies the key to our sanity?

To answer this, we must realize how detaching from our bodies creates misery on our planet. And this has everything to do with the visceral nature of empathy.

Unless you’re a psychopath, you’ve likely felt empathy in your life: that warm feeling you get when you see separated lovers reunited. Or that horrible cringe in our stomach we feel when we see one of those nasty animal abuse videos.

Empathy is a huge cornerstone, and arguably the foundation, of morally correct behavior.

And since empathy is, at root, a felt sensation of connection, we have to look for it inside our bodies.

The quest for interpersonal (and interspecies) empathy, on a global—not just political—level, should be our essential mission. It has to be our cultural “Prime Directive,” if we are to break the spell of separation that we are under.

Aldous Huxley, the famous English novelist (and McKenna’s predecessor as an envelope-pushing intellectual psychonaut) saw the horror of this terrible separation. It could well be said that he was under this very spell.

For him, the boundaries between us are not just social or psychological constructs, but metaphysical absolutes:

“We live together, we act on, and react to, one another; but always and in all circumstances we are by ourselves. […] By its very nature every embodied spirit is doomed to suffer and enjoy in solitude. […]. Words are uttered, but fail to enlighten. The things and events to which the symbols refer belong to mutually exclusive realms of experience.”

Huxley illustrates all too well his nightmare of being reduced to a mental entity, the feeling that he is incarcerated inside his body, existing in solitary confinement until death.

When our naturally open and connected embodiment is twisted into an idea that we are imprisoned in our bodies, it’s hell. Because the essence of imprisonment is isolation.

And it’s no leap of the imagination to see how this prisoner’s mentality can manifest around itself the very opposite of empathy.

The core of this isolating tendency is the illusory separation of body and mind, fueled by the idea that the realms of objects and subjects are ultimately segregated—this is the “perilous thought” I alluded to earlier.

Terrified people might do some nasty things. But it’s the detached individuals that are the most ruthless, and the most violent.

Luckily, not everyone falls victim to this psychotic alienation, because the rationalism of Western culture sparks its own counter-impulse (McKenna’s above-mentioned “antibodies”).

Many Westerners that feel averse to our overly conceptualized frame of cultural reference, experience what McKenna calls “an impulse to return to what is felt by the body.”

This impulse is our nature calling out to us.

Answering this call, for many, means exploring practices such as yoga, meditation, dancing, working with plant medicines, or any of these embodiment-boosting endeavors that we see “spiritual” people undertaking. Coming to HighExistence and reading this article means you yourself probably fall within this category of people that want to free themselves from rigid mental categories.

In following the silent voice of the body, one can learn to break the spell of the overly active mind, that keeps whispering thoughts of alienation into our consciousness.

Therefore it is this inner drive—this pull—that I want to investigate here.

Where does it come from? What is this warm gravitation that glows inside and wants to embrace the others? And with that: how do I relate to my body, when I find myself to be so… mental?

Seeking Sanity by Going Into the Body

Whatever the inner voice is, it clearly connects to the source of empathy and it springs from inside our bodies.

This must be where we dive in.

It’s exceedingly difficult, however, to say what it even is to have—to be—a body.

Yet, by doing exactly this, 20th century French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty created a language to help us say what we all already feel.

By sticking closely to “first person” consciousness, his philosophical style, called “phenomenology,” is uniquely geared to making explicit what is implicitly present in our everyday experience of feeling, touching, and being inside a living, breathing body.

The Phenomenology of Empathy

Speaking from his own sense of embodiment, the Frenchman describes the essential move of empathy: the natural shift from being an “I Am” to a “We Are.”

In his signature way, an example from everyday life forms the beginning of his in-depth analysis of consciousness in action:

“A baby of fifteen months opens its mouth if I playfully take one of its fingers between my teeth and pretend to bite it. And yet it has scarcely looked at its face in a glass, and its teeth are not in any case like mine. The fact is that its own mouth and teeth, as it feels them from the inside, are immediately, for it, an apparatus to bite with, and my jaw, as the baby sees it from the outside, is immediately, for it, capable of the same intentions.”

The infant has an apparent innate sense of “what goes for me, goes for you.” Merleau-Ponty goes on to assert just what this means:

“‘Biting’ has immediately, for it, an intersubjective significance. It perceives its intentions in its body, and my body with its own, and thereby my intentions in its own body.”

The fact that the toddler not only recognizes the other as another “I,” but uses this information to show that it is aware of the intention of the other, shows the depth of the connection that we have through our embodiment: the child already relates his own embodiment to that of the “biting” man.

This example shows us that we are born as inherently empathetic beings. Obviously, the mindfuckery of separation is something that manifests over time.

Let’s look at this conundrum with some close attention.

Escaping the Mother of all Mindf#%ks

Merleau-Ponty’s wording of the problem is razor sharp:

“How can the word ‘I’ be put into the plural, how can a general idea of the ‘I’ be formed, how can I speak of an ‘I’ other than my own, how can I know that there are other ‘I’s,’ how can consciousness which, by its nature, and as self-knowledge, is in the mode of the ‘I,’ be grasped in the mode of Thou, and through this, in the world of the ‘One?’”

The seeming impossibility of transcending the borders of our own ‘selves’ looks like an insolvable puzzle to the most intelligent of minds.

There seems to be no hope in hell that we can ever truly be together when we are faced with the ultimate schism between myself and the other.

Huxley’s nightmare, then, seems inevitable. And many, if not most people who pondered this “hard problem” of philosophy have become depressed, pessimistic, or hopeless.

True empathetic morality looks desperately unattainable.

…“But,” Merleau-Ponty continues,

“…we have in fact learned to shed doubt upon objective thought, and have made contact […] with an experience of the body and the world which these scientific approaches do not successfully embrace.”

What Merleau-Ponty has come to doubt is the scientific reversal of what is perceived and what is thought.

Whereas our minds (and science as a cultural extension of our minds) try to explain the world with concepts, Merleau-Ponty asserts that the experience of the world is in fact primordial and comes before the explanation.

Moreover, reality is understood by the body before it’s understood by the mind. He therefore sees that:

“The physiological event is merely the abstract schema of the perceptual event.”

What Merleau-Ponty demonstrates, simply by paying attention to the way we experience ourselves, is the undeniable primacy of experiential, “pre-reflective” knowledge.

At the same time, this means that after centuries of mental dominance, he demoted the rational knowledge of the mind down to its proper, derivative status.

In doing so, Merleau-Ponty did more than hit a philosophical home run. Ladies and gentlemen, the man just beat the game.

Returning to the example of the “biting man,” we can now see that the way our bodies relate to one another trumps even the most profound attempts of cultural conditioning. “It has taken time to misguide you so completely,” Helen Schucman wisely conveyed, “but it takes no time at all to be what you are.”

In our own bodies, we can sense the intimate causal relationship between our “inside” and our “outside.” And it is through an instinctive extension of our outside that we intuit the other’s inside.

In this way, we as a “we” are born in each other. And so, Merleau-Ponty asks rhetorically:

“If my consciousness has a body, why should other bodies not ‘have’ consciousnesses?”

In this emergence of a group identity that transcends the individual’s egoic sense of self, we can understand what Merleau-Ponty’s insights mean in terms of empathy:

The stronger my awareness of my own embodiment, the more I’ll be able to feel my connection with the rest of you.

Merleau-Ponty indeed goes on to realize that the existence of other “consciousnesses” implies that the perspectives of all these others together create our shared world:

“We must learn to find the communication between one consciousness and another in one and the same world. In reality, the other is not shut up inside my perspective of the world, because this perspective itself has no definite limits, because it slips spontaneously into the other’s, and because both are brought together in the one single world in which we all participate as anonymous subjects of perception.”

What Merleau-Ponty unveils here is the fact that you and I are different expressions of a shared fundamental reality.

In later writings, he describes this overlapping reality as the “flesh of the world.” This flesh is not an ephemeral, metaphysical substance: it consists of our own tangible bodies.

We are made of the same “stuff,” both as each other and as the world around us. Therefore, my body knows that your body knows. As if that weren’t enough, the knowledge of our bodies is rooted in the undeniability of the here and now:

“The word ‘here’ applied to my body does not refer to a determinate position in relation to other positions or to external coordinates, but the laying down of the first coordinates.”

What goes for here also goes for now. Our bodies, in other words, provide for us the very location of existence. That is to say:

Embodiment is presence.

It is this level of awareness that is both the most profound and the most undeniable. And so it is in this sphere of radical certainty that our conscious embodiment allows us—not to conjecture, but to know in our very bones—that this “other” embodied being is also here and now, and that “it” is an “I Am.”

These deep truths of connection have slipped into Western forgetfulness, and need to be re-embodied. Through practices such as meditation, dancing, and yoga, we can unify our own bodies and minds, and awaken our sense of inner connectedness, empathy, and compassion.

A last pinch of nuance, and a dash of alignment

A caveat that should be mentioned at last is that empathy alone won’t get us all the way, as some have intelligently pointed out. Empathy, to my estimation, is necessary but not sufficient. It’s clear that correct reasoning is, and has been, an extremely valuable tool in our human endeavors. This is all to say that empathy, too, can be a form of unawareness, if it’s based on blind dogmatism or ideology. As Jordan Peterson says, we should “use compassion judiciously”.

My main point here, however, is that the body shows us our true moral north, whereas the mind by itself cannot. It’s no coincidence that the words “compassion” and “compass” share a common etymology. Surely, this compass is to be found at the center of our bodies.

Merleau-Ponty reminds us that the body “is that strange object,” through which we can always be “at home” in the world. As the brain resides in our bodies, so too our mental existence must realize its home and grounding in the body. Such “synaesthetic” alignment of our spheres of consciousness brings balance and understanding through connection.

And so we can understand what an ancient yogi once said:

“All beings tremble before violence. All fear death, all love life. See yourself in others. Then whom can you hurt? What harm can you do?”

— Siddhārtha Gautama