Hans • • 24 min read

The Superhero Sutras: Unexpected Dharma Lessons Found While Reading Comic Books

“And for god’s sake, don’t let me ever hear you say, ‘I can’t read fiction. I only have time for the truth.’ Fiction is the truth, fool! ”

― John Waters

“I often like to think that our map of the world is so wrong that where we have centered physics, we should actually place literature as the central metaphor that we want to work out from. Because I think literature occupies the same relationship to life that life occupies to death. In the sense that a book is life with one dimension pulled out of it. And life is something which lacks a dimension which death will give it. I imagine death to be a kind of release into the imagination in the sense that, for characters in a book, what we experience is an unimaginable degree of freedom.”

― Terence McKenna

All right, confession. I LOVE the Marvel movies. It’s not so much the hype in my case though, I actually read all those comics as a youngster (waayyy back in the 90’s).

Being brought up in a stormy environment, the escape that these colorful adventures provided was a welcome sanitarium for my tormented, teenage brain.

I can safely say, though, that I no longer feel alone in this parallel dimension that’s now spawned the “Marvel Cinematic Universe” and the “DC Extended Universe”.

Superhero movies are grossing well into the billions these days. It’s the mania of the moment, and there is no escape. Tons of other sites have been flushing the web with comic book-related content—varying from fascinating facts to personal blogs, theories, comparisons, and, well, mostly just filler. Which gives rise to a question:

Is this superhero movie stuff, that has taken so many of our minds hostage, all just superficial crap, or is there anything of real value to be found in there?

As always, it depends on how you look at it.

First off, it should be no surprise that comics have been in high demand since they were popularized in the United States in the 20th century.

The popularity of the comic book stems from the fact that we humans do not live, as many would have it, in a “scientific” universe of subatomic particles and natural laws, but in a living world of significance.

More specifically, we relate to the world around us as the stage for our life’s stories, to the objects around us as tools for manifesting that story, and to each other as players on the stage for it all. Note how ultimately, even the scientific worldview, as an explanation of the universe, operates as a story; the story-frame is therefore more fundamental than the scientific frame. Thus, we can say that

The psychological format of narrative is the meta-frame that precedes all of intelligible experience.

Another way to see this, is to say that we always perceive situations, as meaningful conglomerates of “sense-data”–that’s not quite it, but I’m using this image to imagine the process that precedes perception. Because we do not consciously perceive sense-data that we then actively make sense of. For there to be anything to make conscious sense of, it has to first already have been put inside a frame of reference that means something to us. And this framing is pre-reflective, meaning that the story always presents itself as a perception, not as creation. This is the very meaning of “meaning”.

Let’s take an archetypal example to illustrate, looking at our own lives. When you went to your high school graduation (or any such a pivotal moment), you didn’t just go into a building made of bricks and steel and glass, and you weren’t simply surrounded by several kinds of other animals, producing sounds by pushing air through their vocal chords, or did you? Much, much more than that,

I bet you were immersed in the overwhelming art of finishing a chapter in your life; tying up loose story ends, and writing cliffhangers that set up the following piece of narrative, encouraging yourself to read on.

And if for whatever reason you didn’t give much meaning to it then, it likely came in retrospect. Perhaps you don’t see meaning often at all—in that case please read on, because I will have more to say on that a little later.

Although we often overlook this psychological reality of narrative meaning, this overlooking should be seen as evidence for the primacy of this ontological plane. And it’s no new insight indeed. Freud saw this, as did the likes of 20th-century French philosophers Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Paul Ricoeur.

In the present day, none other than our much beloved Dr. Jordan B. Peterson, who will make several appearances here today, again draws our attention to this fundamental axis of human existence, connecting significance with narrative as our most basic dimension of meaning.

In his Bible lecture series, Peterson even goes so far as to assert that the metaphysical importance of our narrative psychological structure is not a metaphor: the story we live is phenomenally real for us, in the strongest possible sense. I do not agree with this 100%, and will nuance it later, but his emphasis is surely justified.

In any case, it may be asserted that fiction fits neatly into the way we are wired into our surrounding reality. And the highly accessible style of comics makes that link even smoother.

However, an argument against comics as ideal catalysts for the creative generation of meaning could be that one’s imagination is sparked way more by reading books without pictures.

Though this is likely partly true, it is not entirely relevant.

Because the real attraction comes from the fact that comics provide an ongoing myth of Good And Evil, that feeds our innate need for meaning, order, and direction. Another point to consider is that only about 60% of us can think visually, converting words into pictures in our minds; comic books solve this problem by allowing anyone to vividly envision the story as it unfolds.

All in all, the scales are tipped in favor of the comic book as a useful tool for processing life’s meaning. They can assist in acquiring new understanding for one’s life by providing intelligible structures of significance, on which one can overlay one’s own personal narrative, like a fictional frame of reference.

Here we can see the import of McKenna’s quote at the beginning: to immerse ourselves in fiction is to step into a tutorial testing ground, helping us to shape our reality. You could see a comic then, as a guided fantasy with 2 clear benefits: on one level, it shows us what our imagination is capable of, thereby making its creative powers conscious.

But there is a much more profound, nondualistic level of efficacy to reading comics. It is that, by being guided, we implicitely get a sense of what it means not to be guided. This means that,

To force our imagination is to free it.

The importance of being able to imagine freely can hardly be overstated. One could go so far as to say that it is our imagination that makes humans such unique, dangerous and creative beings as we are.

As Einstein once said: “I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.” Carl Sagan agreed: “Imagination will often carry us to worlds that never were, but without it we go nowhere.”

Surely then, my paper mental hospital can be retrospectively justified!

And so to the paper we must go. Because in the actual comics, which are after all the historical underpinnings of the cinematic efforts, storylines run long and deep, characters become meta-real and frankly, some very strong experiences can be had in those animated pages.

That’s why I want to share with you some of the deep wisdom that can be accrued from reading comic books.

Since Marvel is by far the most successful of the franchises, I’ll focus on their comics (sorry Batman, I still love you!).

So without further ado, get comfy, instruct your mom to provide you with a steady supply of super milk and spidey-cookies, and let’s get cracking on some of the most entertainingly presented dharma talks in the history of dharma talks. Starting us off will be Deadpool, the Merc with a Mouth.

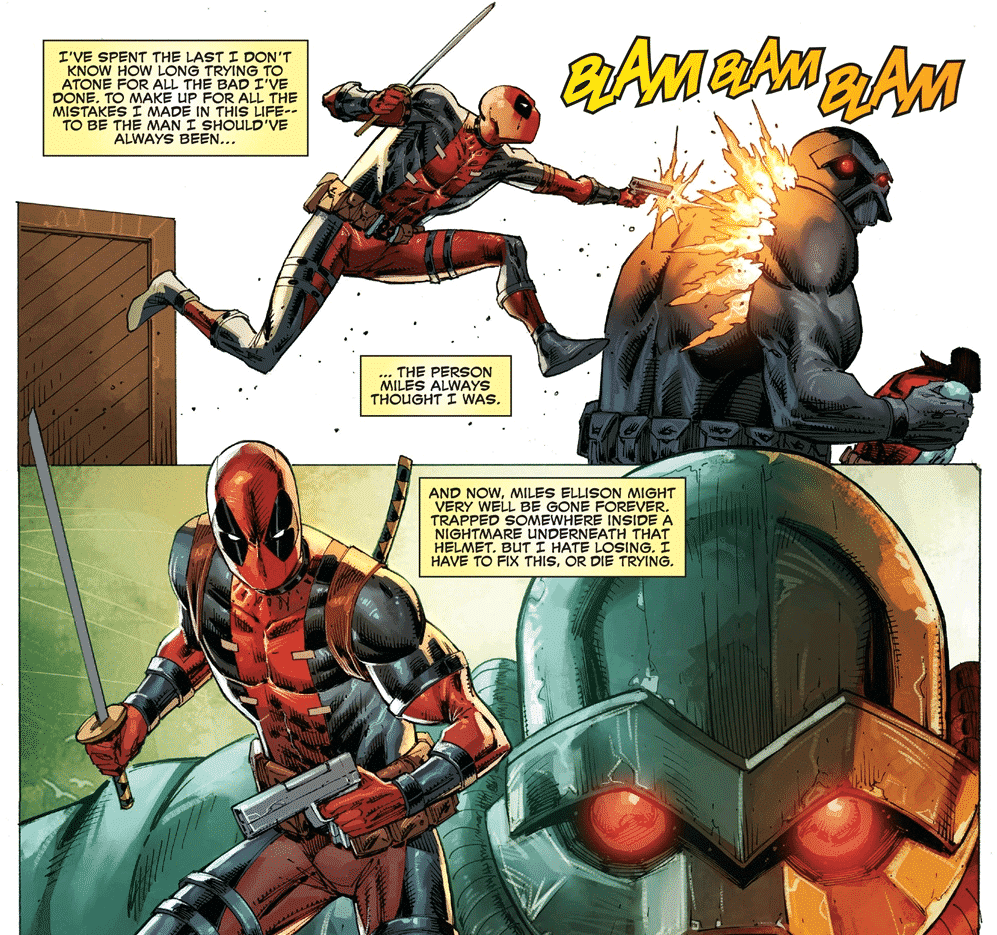

Deadpool: The essence of forgiveness

Deadpool (a.k.a. Wade Wilson), besides being easily the funniest character in the Marvel Multiverse, is:

- a deeply troubled criminal

- a next-level 4th-wall-breaking absurdist

- a chronically ill teleporter

- one-time wielder of the Infinity Gauntlet (making him temporarily all-powerful

- a failed top-secret government experiment

- a stone-cold assassin / mercenary

- and many other wacky things…

….who sometimes tries to be a hero (with highly debatable rates of success).

Deadpool can hardly ever be said to be a “good guy”, although he sure has tried on occasion to rise above the ethical level where he typically resides. So in the final judgment, does that make him a good person or a bad person?

This is no trivial question, as most of us have done things we wish we hadn’t, and perhaps have even hurt people in the process. And if you haven’t yet, you will. Live long enough (or analyze deeply enough), and you’ll discover there’s no way of being in the world without being involved in harming other beings. Most of all the ones you love.

So can we still be good after having dished out pain? One answer lies in the non-personal nature of human suffering.

Deadpool’s lesson #1: Suffering is impersonal.

Suffering is not about us or those we hurt (or that hurt us). The same goes for suffering not concerned with interpersonal relationships, in which case we are the ones torturing ourselves.

But what is suffering? If we take a Buddhist view, it is the agony or unsatisfactoriness that arises when we want the present moment to be different than it is.

Pain is inevitable, but suffering is a choice.

And most, if not all, suffering is caused by human unconsciousness, expressed through our unenlightened behavior.

You can see this kind of behavior in the way we raise our children: we pass on patterns of behavior that are not recognized as patterns. Jordan Peterson correctly observed that “we act out what we don’t understand”. And above all we don’t understand what we don’t see… what we don’t want to see.

For instance, there might be something your father has done (or sometimes does) that you find utterly despicable. This judgment is often a projection, some trait we don’t like about ourselves, which is why we vilify it (cut) and mentally connect it to someone else (paste), casting the threat of judgment far away from us.

The mistake that lies at the core of this is that we already identified with the trait—we falsely assume it reflects poorly on our self, which is why we want to discard it.

But nothing can truly reflect on our self, only on our created self-image or ego.

Let me explain.

To borrow an explanation from Eckhart Tolle, our true nature is to be the “space” for all our experiences, feelings, thoughts, and emotions. Not knowing we are that space is unconsciousness, and out of that unconsciousness a self-image comes, that thinks it is real, and that thinks judgments have an effect on its identity. Fear can thus be seen as an agent of the unconscious.

So if you’re a little Deadpool yourself, and you hurt someone, and that behavior stemmed from a lack of consciousness on your part, you certainly still have a claim to goodness.

That is, if you take it upon yourself to grow into consciousness as soon as you realize you have behaved unconsciously—if you learn from your mistake and seek to improve. And understanding that your lack of consciousness was not your “personal fault” will likely make it possible for you, morally, to move beyond it. And here, we’ve already segued into Deadpool’s lesson #2.

Deadpool’s lesson #2: Don’t let your past mistakes determine your present ethics (or self-image).

Your past cannot make you who you are, only your present actions do. But don’t take my word for it. Take Mooji’s.

Listening to this wonderful teacher has helped me understand something about forgiveness and presence, that can readily be seen by reading Deadpool comics: it’s that you can only be responsible for what you have control over.

Now ask yourself: can you control the past? Right, you can’t. And as harsh (and strange!) as it might sound:

You are not responsible for what you did in the past. Because you cannot be!

Allow me to elaborate. The complete formulation of that thought is “you are not responsible for what you did in the past anymore”. But that addition is relatively trivial because the net result is that the past doesn’t exist, just like the future doesn’t exist (“yet”).

We do of course need to take a form of responsibility for our past mistakes, but that responsibility simply entails a mission to do better now, not a masochistic obligation to carry around our past mistakes forever, as if we had just committed them, nor a nihilistic entitlement to ignore them entirely. The middle way is the best way!

All right, so how can we move on? The answer begins by understanding how the process works.

The function of emotions like guilt or shame is to provide incentive for you to correct your behavior.

Once you use that motivation to correct your behavior, lay the incentivator aside. It’s a tool that has a very specific functional frame. Usage outside of its time and place becomes pathological and does harm rather than good.

To boot, you can’t act correctly in the present if your head is halfway in the past! And that again poses a direct risk of hurting people out of unconsciousness. So to repeat, the two birds you kill with one stone are: stop worrying, and be present.

That simultaneous act of letting past events rest and being present sounds a lot like it just might be the essence of forgiveness. Thanks Wade! On to his roughhousing buddy, Cable.

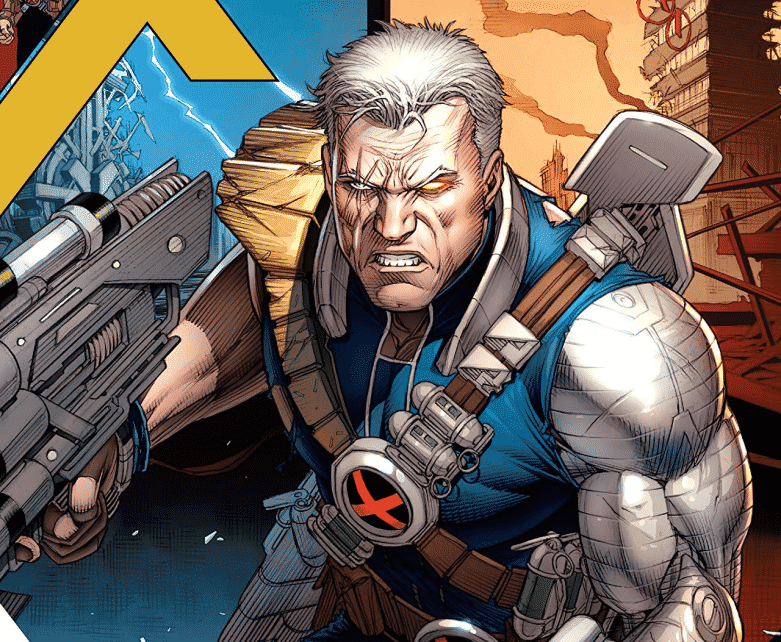

Cable: The healing art of presence

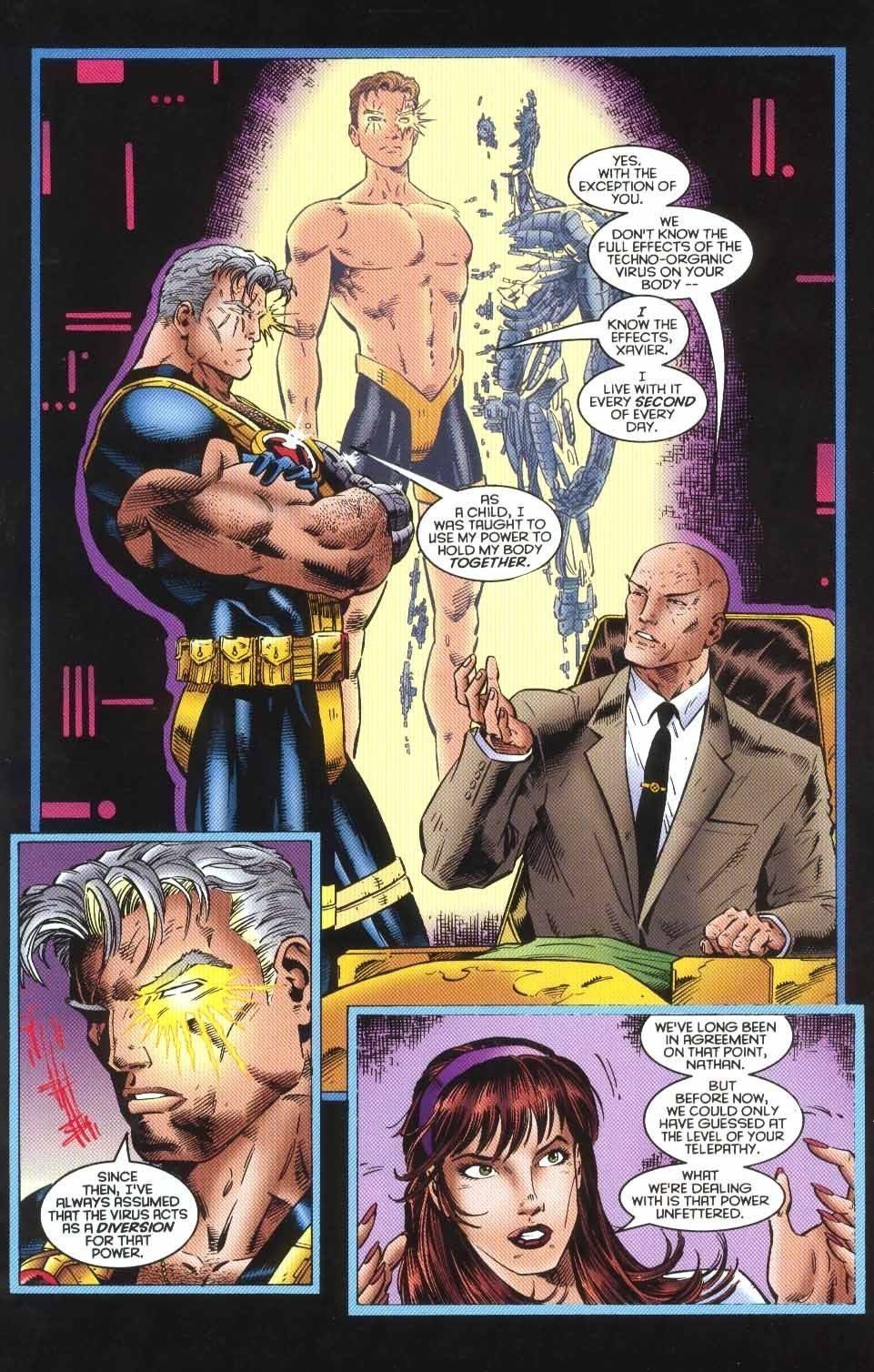

Cable (“real” name Nathan Summers) is quite the character. A vastly powerful psychic, who uses most of his power to suppress a “techno-organic virus” menacing his body and mind—this is a bloke you mess with at your own peril.

This guy almost defeated the Avengers single-handedly (they’re “Earth’s mightiest heroes”, mind you!), and voluntarily seeks out ultra-villain Apocalypse, who is one of the most feared creatures in Marvel’s ficto-space.

The man has no chill.

Skipping for now the less-preposterous-than-we-might-think possibility of an actual techno-organic virus being developed in the future, we can learn a lot “spiritually” from Cable.

Besides being able to kick some serious ass, this future-dwelling, Apocalypse-slaying cyborg-dude represents some confronting Giger-esque truths about our present culture. But I’ll start with a less obvious insight he symbolizes, about the less obvious heroes that walk among us.

Cable’s Lesson #1: Don’t judge a comic….

There are superheroes walking the streets that invisibly cope with PTSD, OCD, ADHD, addiction, and trauma (or any foul-tasting cocktail of these afflictions).

These people work so hard every day that it can rightly be called a miracle that they are still functioning in society. And all this without being recognized for their invisible efforts. Maybe this even applies to you. In varying degrees, it probably applies to all of us.

I have been working my whole life to get to baseline, and now am managing reasonably well to have a decent existence. Perhaps you recognize this story in yourself. Perhaps you even thrive because you have successfully transmuted your leaden struggles into the gold of turning life into a work of art.

But the truth of the matter is, we all suffer. Some more than others. And most suffering remains our own private little hell, hidden behind that curtain of our socially performed plays. And in our internet age, we added digital curtains in front of those mental ones, doubling the divide between our private and social lives.

So what’s the teaching here? I’d say the tale of Cable makes us see that we mostly don’t know our fellow humans’ struggles, by helping us realize that they mostly won’t know ours.

This realization can then help us to show compassion next time someone doesn’t act perfectly well mannered or according to accepted convention, say. And we don’t have to take it so personally (as we saw from Deadpool).

We can ask ourselves instead: what could cause him or her to behave in such a way? And keep the door open for the possibility that he or she might well be a hero in disguise, battling with demons on a day-to-day basis.

This all is certainly no excuse for asshat-behavior, no matter what you’re going through. Like someone once told me, we should carry our misfortunes with some grace.

But we could use a reminder every now and then that we actually don’t know what’s going on in another person’s head. Who knows what Spider-Men hide behind the Peter Parkers that we meet…?

Cable’s lesson #2: Being present is our spiritual master-cure.

The symbol of a technological entity that maliciously adheres onto its host, consuming most of the host’s energy, making him weak. Remind you of anything? Of course our schwifty gadgets empower us greatly technologically, what with all the previously inaccessible things that we can now track, know, calculate, and communicate…

But if the only thing there ever is is the present here-and-now, then never fully being present where we are might not be such a smart idea.

To illustrate (as well as to confess once more), I recently realized that I’ve been suffering from a smartphone addiction. It occurred to me during a weekend sesshin (a Zen meditation retreat), where I kept my phone off for two whole days (not sure if sarcasm). I couldn’t even remember the last time I went that long without.

The relief I felt was profound.

During my stint at college, I’d read about the “disembodied telepresence” of the internet through the likes of Hubert Dreyfus, but now I felt for myself the serene and even intimate quality of undistracted presence. And I tell you, being on your phone for hours a day downright massacres that presence.

If you too feel that diabolical mental itch that says “checkyourphone-checkyourphone-checkyourphone” just a little more often than you’d like to admit, perhaps you could do with a shot of techno-organic-virus-vaccine as well. The cure is both effective and simple:

Turn your phone off for a day.

Laptop too. Turn it all off. And if you feel squeamish about even considering this, you need two days, because your monkey mind’s been chasing virtual bananas for way too long, and could use a break.

Ironically, there are also some apps to limit your smartphone use, but I’d recommend at least a combination of one of those on top of an “off day”, rather than just the app. And of course, a meditation every day keeps the techno-virus away.

It’s no coincidence that Cable was given this dangerous biotech-virus by a being named “Apocalypse”. Cable’s lesson here is a clear warning. And speaking of warnings, this next dude is someone to watch out for, even more so than mighty Apocalypse.

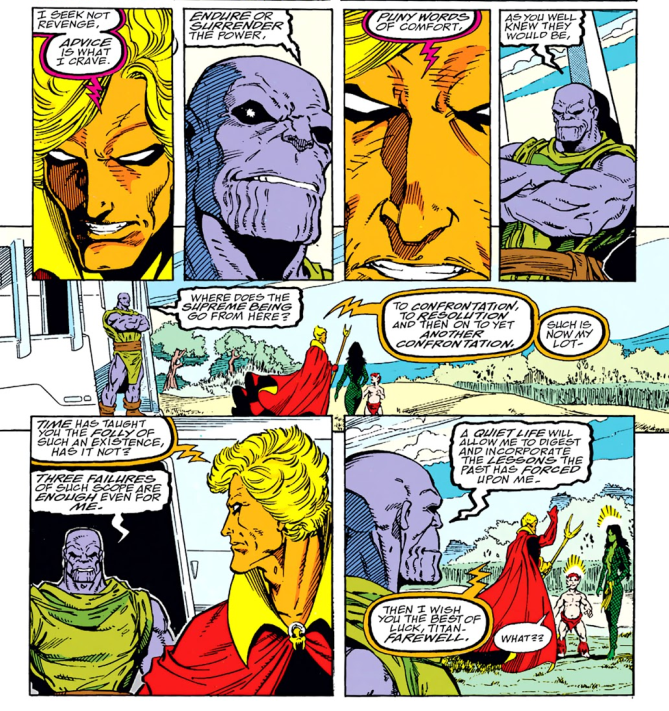

Thanos: Realizing gratitude and grace through existential limitation

[not sure if Marvel Cinematic Universe spoilers!]

Since I’m on a roll, here’s another confession. I’ve always liked the villains way more than the heroes (except for dark heroes like Batman or Wolverine). Perhaps this says something about my own shadow side. As a kid I was always drawing demons and monsters. Something about the dark side held an attraction that was hard to ignore.

I think the bad guys seemed more real to me. I also liked that they always interrupted social structures, which I held accountable for my own misery. But in general, I just found it fascinating to watch the darker proclivities of ourselves acted out in works of fiction.

The deeply human fascination with evil is created when we are taught to stay away from our shadows.

Most children see darkness being manifested at least once in their developing life, but we’re told that “that’s bad”, and it often goes uninvestigated, gets quickly covered up, leaving strongly felt questions unanswered (that was at least my experience, and I suspect, that of many others).

And so the villains we depict in our fictions, as projections of our inner monsters, can be seen as attempts to provide an answer—to understand those parts of ourselves.

This very process of understanding holds a meta-lesson about how we treat our shadow selves (denial, projection, understanding, growth), that can be learnt from any comic book villain. But if you’d have to choose one, Thanos will not disappoint.

Partly based on DC Comics’ Darkseid (enemy to Superman and Batman), Thanos is one of the most archetypal evildoers I ever came across. It’d be no easy feat to find a bad guy more hell-bent on total annihilation and decay.

Needless to say, I immediately loved this guy.

Being a mutant among his own kind, Thanos’ mother tries to kill him straight at birth. In childhood, his peers shun him because he doesn’t look like them. Then, one day, a mysterious young girl persuades him to experiment with killing animals, and later his own kind. And so, the tyranny that is Thanos begins to emerge.

Even Thanos’ name derives from the ancient Greek word “Thanatos” (Θάνατος), which means “death”. His brother’s name, fittingly, is “Eros”, after the Greek god of erotic love. And so too in his story’s arc, “the Mad Titan” is in love with Death itself—personified, as per usual in comic universes, in an anthropomorphic being that embodies the end of life.

As you no doubt have guessed, she appears first as that mysterious little girl, seducing a vulnerable young Thanos, here seen right after killing one of the many women he impregnated (and presumably loved):

I hope you’re not eating while reading this.

So grandiose are his dark ambitions, that Thanos seeks nothing less than omniscience, omnipresence, and omnipotence. Yup, he wants to be god.

His ambition is driven by a deep-seated urge to utterly eliminate existence itself, in a desperate bid to win the black heart of Mistress Death (I know what you’re thinking, this guy must be fun at parties!).

Symbolizing such an unsettling degree of malevolence, Thanos certainly evokes a rare kind of awe in those that read the comics. And on several occasions, the Mad Titan ends up actually getting the ultimate power he so fiercely desires.

Thanos gets to be a supreme being.

On one such occasion, Thanos uses the “Infinity Gauntlet” to possess dominion over space, time, reality, soul, mind, and power. Nothing can stop him but his own arrogance. And so in a slip of attention (after having just replaced the cosmic entity of Eternity itself), the Gauntlet is taken from him by Nebula, and his omnipotence with it.

She is however even less able to maintain control over the Gauntlet, and chaos ensues. A Christ-like being called Adam Warlock finally takes command of the gauntlet, and restores order in the Universe.

One of the first things Adam Almighty does is pay a visit to the dethroned Titan, who has taken it upon himself to become a farmer, reflecting on his past.

Post-omnipotence agriculture is less silly then it might seem. Not only is farmwork known to be highly conducive to happiness, being god is a safe bet for the opposite.

Because what value would the good things in life have, if they were never away from us? It’s kind of like having a friend that’s in your face every second of every day—you’ll start hating that friend in no time flat.

The very definition of value is tied up with the fact of finitude and limitation. We cherish our loved ones because we feel our lives to be very special, limited journeys in conscious existence.

So what good is it to have everything, if what you then have means nothing?

But this god-level of Thanos’ wisdom can be scaled down to a more practical level, yielding even more applicable fruits of philosophy. Because when absolute power renders the very gains of such power valueless, it must follow that the pursuit of that power itself holds a flaw, at least if left unchecked.

Wisdom, then, is knowing where the limits of our control lie (similar to Deadpool and the past). And, connected to that, we can see that the value of love and life lies exactly in the degree to which it can not be attained, only given.

The opposite of Thanos’ sin against this natural law becomes visible as the virtue of acceptance.

What I mean by that is that value is always a property of something that lies beyond us. It’s the compelling emanation of the Other that we perceive. That’s why absolute power vacates the universe of value, and it’s also why life, and love, become valuable and precious precisely when we surrender to our limitations, thereby vulnerably opening ourselves up to receive.

Only in this reciprocity can life, and love, flow. This is something Thanos could not do, and it is why Mistress Death never reciprocated his love.

Carrying such utter pearls of truth, the tale of Thanos is as beautiful as it is tragic. Much more wisdom can be drawn from his adventures, which I absolutely can recommend reading.

But for now a restoration of balance is called for, after these darker ventures of the imagination.

Submitted to the scrutiny of the HighExistence society, I give you…

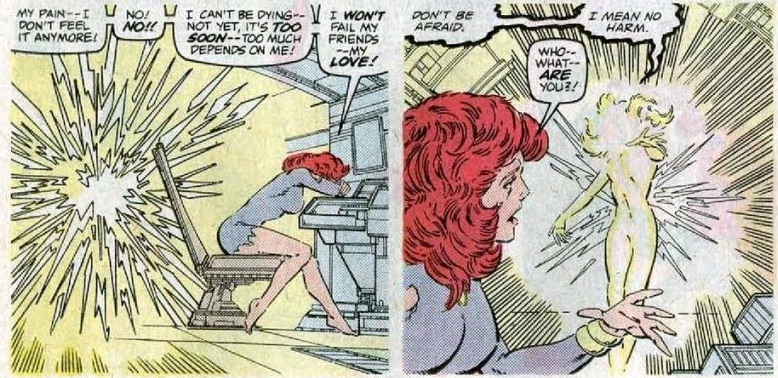

Jean Grey and the Phoenix Force: Sacrifice and rebirth

It’s the force of life itself. It’s a psionic being that transcends all realities across the entire Multiverse. It’s the hope of the hopeless. It’s the all-consuming fire of never-ending freedom.

And It’s a bird!

This is the sutra of the Phoenix Force. This tale teaches us perhaps the noblest lesson yet. It provides guidance in aiming our lives at the highest ethical good, in the best possible way.

“Representing the total sum of all future life born through the multiverse itself, the Phoenix force existed with immense power, serving as a nexus for all psychic energy that has ever, currently does, or will ever exist”, YouTube user ‘ComicsExplained’, explains.

But the “sutra” of this tale comes when the Phoenix Force merges with a mutant called Jean Grey. You might know her from the “X-Men”. Jean is a massively powerful psychic and telekinetic, and somehow, she is the soulmate of the Phoenix Force.

As a child, Jean sees a close friend being hit by a car and is traumatized immediately. As her friend is dying, Jean’s powers first manifest, triggered by the sheer amount of psychological stress. For a moment, she telepathically stops her friend from dying, but then starts to die herself in the process.

Surprised and intrigued, the Phoenix Force picks up on this young mutant’s reality-bending tour de force, and is attracted to the young girl’s spirit. Impressed by Jean’s power, the Phoenix saves her life, and a connection is made between the two.

Years later, when Jean tries to save the X-men by piloting a spacecraft through dangerous radiation, she again is dying and calls out for help. The Phoenix Force appears once more and asks what the mutant wants. Jean tells the Force that she wants to save the X-men, and herself.

The Phoenix grants her wish, making a new body for Jean in the process, and thereby merging part of herself with Jean Grey. Later in Jean’s life, The Phoenix Force comes to actually reside inside her body completely.

Two main things stand out in Jean’s arc. One is her great compassion and willingness to sacrifice herself. The other is the symbolism of the Phoenix which, in Greek mythology, stands for the power of rebirth (in Chinese mythology the Phoenix symbolizes female energy).

So what is the significant connection between sacrifice and rebirth?

Again I turn to Dr. Peterson, who discusses the topic of sacrifice at length in the Bible lectures. If we want to succeed in life, which to a large degree is synonymous to avoiding hell, we have to sacrifice that which we hold most dear, yet stands in the way of our progress. And so the pivotal question becomes, “What is the greatest sacrifice I can make in order to clear my own path forward?”

Sometimes we have to kill part of ourselves in order to survive. Ayahuasca ceremonies are framed this way as well: participants will often experience an “ego death”—a dying of old patterns—to allow for a rejuvenation, a rebirth if you will, to happen. This trade is the meaning of sacrifice and the consequent phoenix, rising anew from the ashes of death.

In the case of Jean, she wants to save the lives of others, and jeopardizes her own in the process. This is a classic feat of heroism, but one can question whether she goes too far.

In a utilitarian sense, we could argue that she is right in saving the X-Men by sacrificing herself, if that means that more people survive because of her sacrifice, than if she had saved herself. But in the case of the childhood friend, her actions almost kill her, to no greater benefit at all.

Where do we draw the line between saving someone and saving ourselves? Peterson warns his listeners by sharing the cautionary tale of lifeguards: they are trained to not save someone, if that person is dragging them down under water. This is exactly what was happening when Jean tried to save her young friend: she was being dragged down into death.

So possessing a clear sense of the greatest possible good in a situation, and the greatest, non-counterproductive, sacrifice aimed at that good, becomes apparent as the correct way of aiming at the best possible outcome in any situation.

But an important caveat here must be inserted, and it is of the kind that holds true to our subject matter. We have to remember that all these stories, just like the concepts in our minds, and the words we use, are of a metaphorical nature. They are not absolute but relative. So what do they relate?

We can think of them as vessels for meaning with an ever-changing import. We can compare a story to a river: the river has a form that changes much slower than the water that flows through it. And so like the river, we should look beyond the form and see the water (i.e. the true meaning) that presently flows through the words and concepts that we use, to perceive the present, and therefore the actual meaning of what’s being conveyed.

These meanings (words, concepts, stories) do create our reality in the sense that our narrative informs our choices, but we must be most wary when we make that transition from the represented to the present.

So, looking at Jean’s example metaphorically, we can see this self-sacrifice in the sense that we give up an image of ourselves: an identification that we are most attached to and so stands most in the way of correct action. It is ego-suicide, not actual suicide.

A strong lesson is excavated here. Should you ever swim into such frightening and chaotic mental waters, always remember to let die the image, not your true self. This is what the McCartneys meant when they wrote Live and let die.

And the thing to remember is that anything that you can hold in your consciousness, you are by definition not.

Lastly, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that we cannot in fact control the outcome of a situation, but only our intentions. And therefore it is more ethically relevant to act according to our best intentions, than to fixate on certain outcomes. This is a stoic insight, that shows us that our power lies in taking responsibility, foremostly, for our own state of mind, and that we should accept what we cannot influence.

A Zen insight connected to this is that intending a certain outcome, is to intend it’s opposite as well. This is too much to go deeply into here, but the wisdom of Zen is to recognize that in our world of duality, it is impossible to create something without thereby creating its polar opposite: before light, there was no shadow. Before good, there was no evil.

You could say that aiming at the highest possible good that we can perceive in a given situation is the best possible intention to have, and that consequently accepting whatever outcome that situation results in, would be the healthiest disposition. And to complete the circle—having those good intentions in the first place is the surest way to being able to accept the outcome, because then we’ll know we acted according to o the best of our knowledge, and to our highest moral standards.

… A moral meta-template for guiding life’s choices. Not too shabby, Jean!

Conclusion

And so we come to the end of this adventure into the philosophy of pictorial literature. A good time to ask, what’s the meta-lesson in all these stories?

It might be that wisdom, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Everything is guru to the wise man. And comics are no exception. But as I pointed out earlier, they do seem to be exceptionally well-geared to provide us with meaning in a most accessible and digestible format, and so deserve special praise from us spiritual warriors.

Even more accessible than comics, of course, are our own lives, though we don’t always act like they are.

But we do live inside the story of our own narrative reality. Therefore, if we look for guidance, we create it ourselves by that very act of looking—we “author” it into being. Because what’s reflected by our searching lights are the things that hold inherent meaning for us, and that can tell us something about ourselves.

Therefore, if you say that life is meaningless, it could well mean that you are not engaged enough in looking for significance.

So the question that beckons all of us, as I see it, is this:

What can I learn from my own story, if I start reading it like a sutra?

[Disclaimer: this article is in no way sponsored by either Marvel or DC Comics]