Jon Brooks • • 32 min read

How to Let Go of Anger: Seneca’s 16 Stoic Techniques

It’s hard to admit, but I never used to know how to let go of anger properly.

As someone who considers themselves “spiritual,” I hid this realization from myself for a long time.

Spiritual people tend to act as if they are anger-phobic even if they don’t claim to be with their words. The spiritual mind is typically full of such incongruities, and if we walk the spiritual path with wisdom our aim should include the noticing of such delusions and blind spots. Without mindfulness there can be no change.

But this is not always easy, and sometimes we fall prey to spiritual bypassing: that is we use spirituality as tool to avoid confronting reality and our own psyche, to push our shadow further into the darkness rather than illuminate and alter it’s icy grip on our life.

One of the main reasons my lack of knowing how to let go of anger was invisible to me for so long was because I didn’t act out my rage with violent intent. My pre-frontal cortex, thank God, prevented me from hitting people or smashing up the house.

Instead, my anger would leak out like a noxious gas—hard to notice, but still toxic to myself and those around me. While my anger was not explicitly noticeable behaviorally, it was certainly a felt phenomena by those whose company I shared. I have irreparably damaged relationships because I did not know how to let go of anger effectively.

Even when you have an inkling that you may have a problem, it’s still a sour pill to swallow. Nobody wants to think of themselves as angry. Nobody wants to think of themselves as someone who struggles to regulate their emotions. When I started seeing how much of a slave I was to my anger, I felt defected. But I also felt motivated to overcome it.

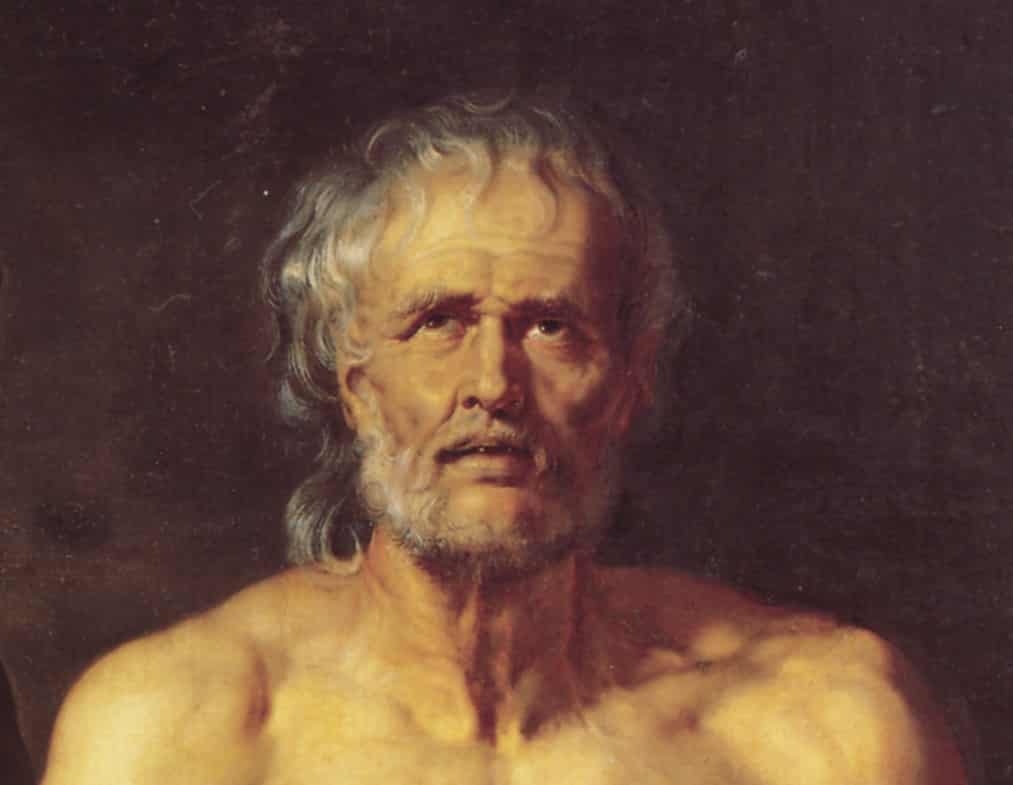

The biggest myth about letting go of anger is that only certain anger-prone people experience it. Seneca the legendary Stoic philosopher, believed that anger does not discriminate between character types at all:

Anger summons even men gentle and peaceful by nature to acts of cruelty and violence. Just as physical robustness and careful attention to health are of no benefit against plague (for it attacks the weak and the strong without discrimination), so men of a calm and relaxed nature are as much at risk from anger as those who are more excitable, and the more it causes a change in these, the more it brings shame and danger upon them.

Take a moment to think about the negative effects of anger both in your own life and in the world at large.

Did you know that each week in the UK, two women are murdered because of domestic violence, and 400 people who have attended a hospital for domestic abuse commit suicide each year?

This fact represents the hidden domestic world of anger, where it is the most dangerous because it is the least visible.

How many deaths could have been avoided if people learned how to let go of anger? How many families could be saved? How many wars avoided and bad decisions averted?

Is it unreasonable to assume that if everyone on this planet were suddenly given the power to let go of their anger effectively and wisely, most of the unnecessary suffering would be dispensed with?

I believe so, and so I felt it was my moral obligation to write a post sharing Seneca’s advice on how to let go of anger with integrity and wisdom. The advice contained herein has been very useful in my own journey.

While this article does focus heavily on the emotion of anger, the post in a more general sense contains much information about emotional mastery.

If you are able to learn how to let go of anger, you will have tamed the wildest of the emotions and will find other mind states much easier to manage. So even if you don’t think you have a major issue with anger, read on as you will find many important insights from Seneca on emotional intelligence.

Note: I have tried to keep Seneca’s writings on anger as coherent and well-ordered as possible and have avoided breaking them up into fragments unless necessary. Seneca is the true master of the topic on anger and his quotes should be read in full. All quotes were taken from Seneca’s book On Anger, which can be found in his Dialogues and Essays.

Seneca’s 16 Stoic Ways for How to Let Go of Anger

1) Recognize that anger is rarely useful

The first step for letting go of anger is simple: recognize how problematic this emotion is. If you think anger is frequently acceptable, how will you ever learn to control it?

Seneca writes:

We shall prevent ourselves from becoming angry if we repeatedly place before our eyes all anger’s faults and form a proper judgement of it. It must be tried before the jury of our own hearts and found guilty; its faults must be searched out and dragged into the open; in order to reveal its true nature, it should be compared with the worst evils.

In the West anger does not always have a bad reputation. Aristotle, a juggernaut of Western thought, believed that anger is not always bad. If one is angry at the right time and in the right context then anger can sometimes be justified. In theory, this is true. There must be cases in hindsight where anger was used with wisdom and if analyzed by a group of onlookers might seem justified, but the problem with this idea is that its real-world implications are not so easy to put into practice.

- Who decides when anger is justified?

- Is an angry person capable of sound and wise judgement?

- Do angry people always feel justified in being angry regardless if they actually are?

Seneca thought that anger was a vice with few, if any, exceptions. The fact that Seneca wrote a book just on anger shows how much importance he gave to this emotion. The three main reasons Seneca lists for this reasons are as follows:

a) Anger makes you a slave:

Surely every man will want to restrain any impulse towards anger when he realizes that it begins by inflicting harm, firstly, on himself! In the case of those who give full rein to anger and consider it a proof of strength, who think the opportunity for revenge belongs among the great blessings of great fortune, do you not, then, want me to point out to them that a man who is the prisoner of his own anger, so far from being powerful, cannot even be called free? In order that each man may be the more watchful and keep a careful eye on himself, do you not want me to point out that, though other vile passions affect only the worst sort of men, anger creeps up even on enlightened men who are otherwise sane? This is so much the case that some men call anger a proof of frankness, and it is popularly believed that the most obliging people are particularly liable to it.

When we are angry, we are a slave to that anger. We are more likely to make mistakes that we will end up regretting later. Anger creates future blindness beyond the immediate moment, making our rational or higher selves a complete slave to a lower form of consciousness.

The only other thing comparable to anger in this nature is the sex drive. Unplanned pregnancies occur, for example, when both partners do not use contraception in the heat of the moment, forgetting the long-term consequences. Anger similarly makes us act in a way that feels gratifying in the short term, but takes us away from our long-term ideals. Anger, like sex, is a primal emotion. Its uses would have been more beneficial in a primal world.

b) Anger cannot be slowed down

For though the rest of the passions may be amenable to such postponement and may be cured at a slower pace, this one, with its rapid and self-propelled violence, does not proceed gradually but reaches its full scope the moment it begins; unlike other vices it does not tempt the mind but carries it off by force, and drives on those who, lacking self-control, desire the destruction, it may be, of everyone, spending its rage not only on the targets of its aim but on whatever happens to cross its path. The other vices drive the mind on, anger hurls it headlong. Even if a man may not resist his passions, yet at least his passions themselves may cease: anger intensifies its force more and more, like lightning and hurricanes and all other phenomena beyond control, as they do not simply move but fall.

Anger, as Seneca defines it, is a binary emotion. The moment you realize you are angry, you are already under its control. The emotion of anger has a forward momentum that is far more intense than other emotions. When you are in the middle of acting out anger, you are unconscious to any other course of action, and are already moving headlong into a path of destruction and chaos. You don’t want to be calm when you are angry; anger justifies its own existence. It feels good to rage, to vent. Anger can be addictive.

c) Anger is contagious

Anger is also notable for its ability to spread through a social group more than any other passion. Seneca writes:

In short, the other vices seize individuals, this is the one passion that sometimes takes hold of an entire state. Never has an entire people burned with love for a woman, no state in its entirety has placed its hope in money or profit; ambition seizes men one by one on a personal basis, lack of self-restraint does not afflict a whole people; often they rush to anger in one mass. Men and women, old men and boys, the nobility and the rabble are in accord, and the whole crowd, spurred on by a handful of words, succumbs to a greater passion than the one who spurred them on; they rush at once to weapons and firebrands, declaring war on their neighbors or waging it against fellow citizens; entire houses are consumed by fire, root and branch, and the man who was lately admired for his eloquence and held in high esteem is now the victim of his own followers’ anger.

This is, of course, mob behavior. Making humans work very well together in organized cohesion typically takes infrastructure and management. But when enough anger is present, the individuals become one larger angry organism and seem to work perfectly together with the unified vision of havoc.

2) Make the attainment of a tranquil mind your highest goal

After you see clearly the destructive nature of anger and how important letting go of anger is, you will start to lessen your attachment to it. But disliking anger—pushing away from it—is only half the battle. We also need some end of goal to move toward. That goal, according to Stoic philosophy of life was the attainment of tranquility.

“There is no more reliable proof of greatness,” writes Seneca, “than to be in a state where nothing can happen to make you disturbed.” The fully enlightened Stoic, referred to as the Stoic sage, was able to remain at peace regardless of whatever circumstance he found himself in. The stoic sage then, would not experience full-blown anger since nothing would be able drive him to that state, let alone force him to act out his anger.

3) Choose your friends wisely

There’s a famous self-improvement maxim that asserts one becomes the average of the five people one associates with the most. It’s not clear where this idea originated from, but Seneca realized this truth thousands of years ago when he wrote:

As we do not know how to endure injury, let us take pains not to receive any. We should live with a very calm and compliant person, one not at all given to worry or peevishness; we adopt our habits from our associates, and, as certain bodily diseases spread to others from contact, so the mind passes on its faults to those nearest: the drunkard draws his fellow drinkers into a love of neat wine, shameless company perverts even the strong man who has a will of iron, greed transfers its poison to its neighbors. The same principle is true of the virtues, but to opposite effect, namely that they exert a good influence on all they are in contact with; no suitable location or more healthy climate benefits an invalid as much as association with better company benefits a mind that lacks strength.

Seneca is saying that corruption can spread, but so can virtue. The main difference being that it is easy or closer to our default to have some level of corruption. For one virtuous individual to spread their virtue into a band of convicts that virtuous person must have incredible strength of character.

If you know you are prone to anger, then you will be foolish to surround yourself with friends who trigger that anger or provoke you. Part of raising your own children, according to Dr. Jordan B. Peterson in his fantastic book 12 Rules for Life is to not make them provoke your inner monster. Seen as you can’t choose the temperament of your children, part of your job as a parent is to mould your child into someone you would be pleased to be with.

When choosing your friends, Seneca instructs:

Choose men who are honest, easygoing, and have self-control, the sort who will not arouse your anger and yet will tolerate it; more useful still will be men who are amenable, kind, and charming, but not to the point of flattery, for those given to anger are offended by fawning agreement: I, at any rate, had a friend who was a good man, but too quick to feel anger, and it was no more safe to flatter him than to abuse him.

4) If you have a hot temper, use art and music to calm the mind

Hot-tempered people should avoid as well studies that are demanding, or at least engage in ones not liable to end in exhaustion; the mind should not occupy itself with hard tasks, but should be given over to pleasurable arts: let it be calmed by reading poetry and charmed by the tales of history; let it be treated with a measure of gentleness and refinement. Pythagoras would bring peace to his troubled spirit with the lyre; and who is unaware that the bugle and trumpet stir the mind, just as certain songs have a soothing effect that relaxes the mind? Disordered eyes find benefit in green objects, and weak sight finds certain colors restful but others dazzling, and therefore blinding: in this way pleasant pursuits prove a balm to the troubled mind.

If you are prone to frustration and find it hard to let go of anger, Seneca believes finding art or music that soothes you will prove beneficial in your pursuit of a tranquil mind. Music is a universally loved art-form, and everyone has at least a few songs that will make them feel more at peace when they hear them.

If you suffer from a hot-temper, Seneca would advise you have and ample supply of music at hand that you find calming. Besides this, nearly any type of art can be calming. The philosopher Alain de Botton has an excellent book called Art as Therapy which outlines which types of art can manage different psychological ailments.

5) Learn your anger triggers and stop it early

If we practice mindfulness (read my ultimate guide here), we will not only be able to detect the macro patterns that trigger our anger, but also to see the specific thoughts arise that lead to the emotion of anger. The benefit of this is that we will be able to catch and neutralize them far earlier.

Speaking personally, here is the typical pattern of my anger:

- Someone acts in a way that I do not want them to act.

- I ignore their reasons for acting, and conclude they must disrespect me.

- My mind floods with images of this person devaluing me and seeing me as a joke.

- A tension builds up in my body, a heavy sludge of frustration flows through my veins.

- I realize that I’m becoming angry, and want the feeling to go away. I hate being angry. Now I am angry that someone made me feel angry, that they disturbed my inner peace. They really disrespect me.

- I begin thinking of the ways I can take revenge or “teach a lesson” to the person for disrespecting me. They won’t get away with this. My self-image inflates to epic proportions.

- I notice my anger building, and put an emotional lid on my boiling saucepan. I try to keep calm and avoid giving them the satisfaction of making me be angry. I become quiet and bottle everything up inside.

- This doesn’t work, and I say or do something that’s passive-aggressive or destructive.

- Conflict ensues. I am unable to escape the conflict.

The more mindful we can become about our anger, the more we will be able to slow it down in the earliest stages of its onset. This is arguably one of the most effective strategies that teaches us how to let go of anger.

Seneca advises:

And so the best course is to treat the sickness as soon as it becomes apparent, at that time as well giving oneself the least freedom of speech and curbing emotion. Again, it is easy to detect one’s passion, as soon as it arises: diseases have symptoms as their harbingers. Just as the signs of storm and rain precede them, so there are certain messengers that herald anger, love, and all those tempests that batter the soul. Those who are subject to epileptic attacks realize a fit is coming on if warmth leaves their extremities, if their sight wavers, if their muscles start to twitch, if memory fails and the head begins to swim; accordingly they try the usual remedies to prevent the malady at its beginning, and by smelling or tasting something they drive away whatever it is that makes them unconscious; or apply hot poultices to battle against coldness and stiffness; or, if this treatment has no effect, they separate themselves from the crowd and fall where no one may witness it. It is an advantage to know one’s own illness and to destroy its strength before it has scope to grow. Let us take note of what it is that particularly provokes us: one man is roused by insulting language, another by insulting behavior; this man desires special treatment for his rank, that one for his good looks; this one wishes to be considered a fine gentleman, that one a great scholar; this one cannot bear pride, that one inflexibility; that one does not consider his slaves worthy of his anger, this one is cruel in his own home but mild outside; that one judges it an offense to be put up for office, this one an insult not to be put up. Not all men are wounded in the same place; and so you ought to know what part of you is weak, so you can give it the most protection.

6) Resist the impulse to be curious

Your best friend said something about you. Want to hear it?

Your partner was texting someone attractive. Want to read their messages?

Someone whispered something at you when you walked past. Want to know what they said?

WHY?

If your goal is to maintain a tranquil and undisturbed mind. Why would you want to seek out information that will likely cause you despair?

I’m sure you have your reasons for wanting to be curious in this way.

I hate to admit it, but in the past I have read my girlfriends messages on their phone. My curiosity became so strong that I could not resist to urge “to know.” This was a stupid mistake. Not only did I break their trust by doing this (I told her immediately), but I also sacrificed my tranquility of mind. Men and women flirt, and this is healthy and normal. Even in the best relationship in the world, you will likely find ways your partner acts that triggers your jealousy or insecurities. One impulsive drive to be curious can ruin an otherwise healthy relationship.

The ever-wise Seneca advises us to resist the urge to be curious if we want to keep a peaceful mind:

It does not serve one’s interest to see everything, or to hear everything. Many offenses may slip past us, and most fail to strike home when a man is unaware of them. Do you want to avoid losing your temper? Resist the impulse to be curious. The man who tries to find out what has been said against him, who seeks to unearth spiteful gossip, even when engaged in privately, is destroying his own peace of mind. Certain words can be construed in such a way that they appear insulting; some, therefore, should be abandoned, others scorned, others condoned. Anger should be circumvented in many ways; let most affronts be turned into amusement and jest.

7) Don’t seek reasons to be angry

Anger sometimes can feel perversely good. It’s almost freeing. When one is angry, low-confidence, and social anxiety disappears. I may be afraid to speak up in public or do silly things on the street. But if you make me rage in a frenzy of hatred, I am capable of shouting at the top of my lungs in front of everyone without a care in the world. I have seen the shyest among us turn into social savages when prompted into anger.

For the reason, we can sometimes actively seek reasons to be angry.

Very many men manufacture complaints, either by suspecting what is untrue or by exaggerating the unimportant. Anger often comes to us, but more often we come to it. Never should we summon it; even when it falls on us, it should be cast off.

Instead, seek reasons to be calm.

8) See yourself in the offender

How many times have you acted badly? Have you ever said mean things to someone which you later regretted? Have you ever acted violently? Have you ever manipulated someone? As humans, we are all more similar than we are different. We have all acted in corrupt ways, and then realized later that our free will is not so free, but is in truth owned to a large degree by our passions.

When we get angry, we are typically outraged at the actions of others. But in all likelihood, we have acted just like them at some point in the past. So the next time someone really annoys you, Seneca advises you see yourself in them:

No one says to himself, ‘I myself have done or could have done the thing that is making me angry now’; no one considers the intention of the person who performs the action, but just the action itself: and yet it is to this person that we should turn our attention, and to the question whether he acted intentionally or by accident, under compulsion or mistakenly, prompted by hatred or by a reward, to please himself or to oblige another. The offender’s age is of some account, as is his status, so that it becomes either kindness or expediency to endure his behavior with patience. Let us put ourselves in the position of the man who is making us angry: in point of fact it is an unjustified estimate of our own worth that causes our anger, and an unwillingness to put up with treatment we would happily inflict on others.

Trying to see yourself in others is not only a great exercise for how to let go of anger, it’s also very good exercise for combatting social anxiety.

9) Just wait

Seneca says, “The greatest cure for anger is to wait, so that the initial passion it engenders may die down, and the fog that shrouds the mind may subside, or become less thick.”

It’s often the most common sense piece of advice, but simply waiting or counting to ten is one of the best things we could ever do when angry. Emotions do not last forever. They are transient. We know this, and in knowing this we can simply wait for them to pass.

Seneca explains:

Some of the affronts that were sweeping you off your feet will lose their edge in an hour, not just in a day, others will disappear altogether; if the delay you sought produces no effect, it will be clear that judgement now rules, not anger. If you want to determine the nature of anything, entrust it to time: when the sea is stormy, you can see nothing clearly.

If you are feel yourself about to get angry, remove yourself from the situation that is provoking you, or withhold all actions until you feel yourself in a completely tranquil state of mind.

10) Do battle with yourself

One of the key principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a psychological intervention derived from stoicism which is used to effectively treat depression and anxiety, is the self-challenge.Typically thoughts carry us away with them. In CBT, we are instructed to challenge the validity of thoughts. Are they rational? Are they accurate? Do they contain any distortions?

When it comes to anger, Seneca suggests we do something similar both with thoughts and our bodies:

Do battle with yourself: if you have the will to conquer anger, it cannot conquer you. Your conquest has begun if it is hidden away, if it is given no outlet. Let us conceal the signs of it, and as far as is possible let us keep it hidden and secret. This will cost us a great deal of trouble (for it is eager to leap out and inflame the eyes and alter the face), but if it is allowed to display itself outside ourselves, it is then on top of us. In the lowest recess of the heart let it be hidden away, and let it not drive, but be driven. Moreover, let us change all its symptoms into the opposite: let the expression on our faces be relaxed, our voices gentler, our steps more measured; little by little outer features mould inner ones.

By doing battle with ourselves, we may be able to change the course of our anger. We can think the opposite of the thought that drove us to this state and change our posture to that of a calm person. Ultimately, this power of this technique will come down to the level of willpower you have and the amount of energy you can muster in your pursuit to letting go of anger.

11) Build a collection of anger case-studies

“Biographies are the best self-help books.”

— Tal Ben-Shahar, Ph.D., Author of Happier

If you read the works of the Stoics you will find plenty of recited stories from history. Seneca was fond of using real-world examples to explain his philosophy. According to Seneca, it would be wise to make a mental collection of people who’ve let anger get the better of them and also of those who managed to control their anger with dignity. Then when you find yourself in a difficult situation, you can call to mind the stories for instruction on what to do and what not to do.

You can also look at your own biography. Dr. Jordan B. Peterson has a personal development writing program called Self Authoring that helps you deconstruct your past. You could use this program to analyze times in the past that anger got the better of you and the consequences that followed, but also the times that you managed to avoid getting pulled into anger.

12) Develop tolerance

It sounds so simple. Develop tolerance. But it’s an incredibly difficult virtue to cultivate. Tolerance is so tricky to enact because there are times when we should absolutely not tolerate another person’s behavior. If someone is crossing our boundary and we become too tolerant then we may overtime get bullied or taken advantage of.

On the other hand, being overreactive and overly sensitive to others can make you overly intolerant of wrongdoings, which carries its own unique disadvantages. Intolerance when carried too far can make the world seem oppressive and tyrannical as well as putting one’s own position as that of a victim on some level. Some segments of the social justice movement, for example, seem extremely intolerant to even minor intolerance. As is the case with many movements of opposition, the same structure is inherited as that which it tries to change. People who have a history of being bullied an also be highly reactive to slights from others and come across as intolerant.

Seneca on forgiving people for their anger:

Many have pardoned their enemies: should I not pardon laziness, carelessness, or chattering? A child should be excused by his age, a woman by her sex, a stranger by his independence, a servant by the bond of familiarity. Someone gives offense now for the first time: let us consider how long he has given pleasure; someone has given offense at other times and often: let us tolerate what we have tolerated for a long time. He is a friend: he acted against his better judgement; he is an enemy: he acted within his rights. Let us put our trust in one who is sensible, and show understanding towards a fool; whoever the man is, let us say to ourselves on his behalf that the wisest men have many faults, that no one is so observant that his attention to detail does not occasionally falter, that no one is so ripe in judgement that his self-possession is not driven by misfortune into some heated action, that no one is so afraid of giving offense that he does not stumble into it while seeking to avoid it.

On remaining unshaken by another’s anger:

Let us consider how many times when we were young men we did not show enough care in duty, or enough control in speech, or enough restraint in drinking. If a man is angry, let us give him time to come to realize what he has done: he will be his own critic. Suppose in the end he deserves punishment: that is no reason for us to offend on an equal scale. There will be no doubt that whoever regards his tormentors with scorn separates himself from ordinary humanity and towers above his fellow men: it is the mark of true greatness not to feel when you have received a blow. So the huge wild beast calmly turns to survey barking dogs, so the wave dashes to no effect on a great cliff. The man who does not become angry maintains his stance, unshaken by harm; the man who does become angry loses his balance. But the man whom I have just placed beyond the scope of all damage holds in his embrace, as it were, the highest good, and not only to man but to Fortune herself makes this response: ‘Do whatever you will, you are not capable of undermining my serenity. This is forbidden by reason, to which I have entrusted the guidance of my life. The anger I feel is more likely to do me harm than any wrong you may do me. And why should it not do more? Because its limit is fixed, whereas there is no telling to what lengths anger may carry me.’

On acceptance and tolerance:

Why do you tolerate a sick man’s lunatic behavior, a madman’s crazed words, or children’s petulant blows? Because, of course, they appear not to know what they are doing. What difference does it make what fault it is that makes a person behave irresponsibly? Irresponsibility can be used to defend anyone’s conduct. ‘Well, then,’ you say, ‘shall that man go unpunished?’ Allowing for the fact that this is your wish, it will still not happen; for the greatest punishment of wrongdoing is having done it, and no one is punished more severely than the man who submits to the torture of contrition. Again, one should take into account the boundaries of our human condition, if we are to be fair judges of all that happens; and there is no justice in blaming the individual for a failing shared by all men. Among his own countrymen the Ethiopian’s coloring is not remarkable, and among the Germans hair of reddish color that is tied in a knot becomes a man: you are to judge no feature peculiar or shameful in one man, if it is common to his whole race. Even those instances I have mentioned can be defended by the custom of a particular portion or corner of the world: consider now how much more justice consists in pardoning those qualities that are common to the entire human race. All of us are inconsiderate and imprudent, all unreliable, dissatisfied, ambitious—why disguise with euphemism this sore that infects us all?—all of us are corrupt. Therefore, whatever fault he censures in another man, every man will find residing in his own heart. Why do you find fault with that man’s pale skin, or this man’s leanness? These qualities spread like plague. So let us show greater kindness to one another: we live among wicked men through our own wickedness. One thing alone can bring us peace, an agreement to treat one another with kindness.

13) Heal rather than punish

When one expresses anger toward us, it’s not uncommon to want to take revenge, to punish the person for their wrongdoing. This is the idea behind the prison system. Someone breaks the law, and we deal with that law breaking by punishing them in hopes that they will reform and stop acting in harmful ways. What is usually the case, however, is that people come out of prison as worse offenders than when they went in.

More and more in progressive countries we are seeing prison systems that aim to heal rather than punish—to rehabilitate rather than simply condemn. This is a very constructive attitude when carried over to interpersonal situations involving anger as it puts the “victim” in a more powerful position, as healer rather than punisher. The act of revenge carries with it connotations of anger. If anger is as bad as we’ve established in the intro, surely the goal should be to learn how to let go of anger both in ourselves and others.

Seneca writes:

How much better it is to heal a wrong than to avenge one! Vengeance takes considerable time, and it exposes a man to many injuries while only one causes him resentment; we always feel anger longer than we feel hurt. How much better it is to change our tack and not to match fault with fault! No man would consider himself well balanced if he returned the kick of a mule or the bite of a dog. ‘Those animals’, you say, ‘do not know they are doing wrong.’ In the first place, how unjust is the man who thinks that being a human debars one from forgiveness! Secondly, if the fact of their lacking judgement exempts all other creatures from your anger, you should place in the same category every man who lacks judgement; for what does it matter that he does not resemble dumb animals in his other qualities, if he does resemble them in the one respect that excuses dumb creatures however they offend, a mind shrouded in darkness? He did wrong: well, was it his first offense? Will it be his last? There is no reason for you to believe him, even if he says ‘I will not do it again’: not only will he offend but another will offend against him, and the whole of life will be a cycle of error. Unkind behavior should bring out our kindness. Words that usually prove most salutary in time of grief will have the same effect also when a man is angry: ‘Will you cease at some time or never? If at some time, how much better is it to abandon anger than to wait until it abandons you! Or will this inner tumult continue for ever? Do you see how troubled a life you are condemning yourself to? For what will a man’s life be like if he is constantly swollen with anger? Moreover, once you have truly inflamed yourself with rage and repeatedly renewed the causes that give impetus to your passion, of its own accord anger will take its leave and time will reduce its strength: how much better it is that you defeat anger than that it defeats itself!’

14) Turn anger into appreciation

When someone triggers us into anger we tend to forget all of the positive aspects of that person’s character and deeds, and also all the positive aspects of our life. Our world shrinks down into single-pointed rage.

By practicing gratitude, both for the lessons we might learn from encountering a provocative foe, or the good things that angry person has done for us in the past, we can transmute our anger into appreciation.

No one who looks at another man’s possessions takes pleasure in his own: for this reason we grow angry even with the gods, because someone is in front of us, forgetting how many men are behind us and what a massive load of envy follows at the back of those who envy a few. But so arrogant are humans that, however much they have received, they take offense if they might have received more. ‘He gave me the praetorship, but I had hoped for the consulship; he gave me the twelve fasces, but he did not make me a regular consul; he was willing to have the year named after me, but let me down over the priesthood; I was elected as a member of the college, but why just of one? He crowned me with honor before all Rome, but contributed nothing to my finances; he gave me what he was obliged to give to someone, he took nothing from his own pocket.’ Rather show gratitude for what you have received; wait for the remainder, and be happy that your cup is not yet full: it is a form of pleasure to have something left to hope for. You have outstripped all others: rejoice in coming first in the judgement of your friend. Many outstrip you: reflect on the fact that more are behind you on the course than in front of you. You ask what is the greatest failing in you? You keep accounts badly: you rate high what you have paid out, but low what you have been paid.

The next time you feel a storm swirling inside you, direct your mind to the positive aspects of the situation.

Ask:

- What am I grateful for right now?

- What lessons could I learn from this situation?

- What good has this person done for me in the past?

- Could I be grateful for this situation in 10 years?

15) Stop being a diva

This is not a joke point. Many of us in the West have way too much diva in us. We live in a world of comfort and luxury. This eventually softens us and makes us weak and thin-skinned. Many of us grow up spoilt and learn to expect things from the world then get angry when those expectations are not met. This can be problematic, especially when we expect things that are at odds with the way things really are.

Sometimes we get cut off by bad drivers; sometimes we misplace our keys; sometimes our friends make inappropriate jokes. These are all parts of life, and if we get angry every time our expectations about reality are not met we will surely live an angry existence.

Seneca warns us against being a diva:

It makes you angry that a slave has answered you back, or a freedman, or your wife, or a client: you then go on to complain that the state has been deprived of the freedom of which you have deprived those under your own roof. Again, you call it willfulness, if a man has said nothing when questioned. Let him speak, or remain silent, or laugh! ‘In front of his master?’ you say. Yes, in front of the head of the household, too. Why do you shout? Why do you rant? Why do you call for a whip in the middle of dinner, just because slaves are talking, just because in a room with a crowd of guests big enough for an assembly there is not the silence of the desert? Your ears are not simply for hearing tuneful sounds, mellow and sweetly played in harmony: you should also listen to laughter and weeping, to words flattering and acrimonious, to merriment and distress, to the language of men and to the roars and barking of animals. Why do you shake, you wretch, at the shout of a slave, at the clashing of bronze, or the slamming of a door? For all your sensitivity, you have to listen to thunderclaps. Apply what has been said about your ears to your eyes, which suffer from just as many qualms, if they have been badly trained: a stain offends them, or dirt, or tarnished silver, or a pool whose water is not clear to the bottom. These same eyes, in fact, which do not tolerate marble that is not variegated and shining from recent rubbing, or a table that is not marked by many veins, that will only have under foot at home floors more precious than gold—these eyes out of doors observe quite calmly overgrown and muddy paths, and the majority of people they encounter in a state of dirtiness, and the walls of tenements cracked and full of holes and out of line. What reason is there, then, other than this for those people not being offended out of doors but annoyed in their own homes: that on the street our state of mind is calm and accommodating, while under our own roof it is churlish and critical?

How can we learn to stop being a diva? One of the most powerful practices in the Stoic toolkit is what’s called negative visualization. The stoics often visualized the worst-case scenario and all the things that could go wrong so that they would be ready for whatever may come, but also grateful for the times when negative occurrences were absent.

Arguably the most famous stoic Marcus Aurelius wrote about his negative visualization at the start of each day in his masterpiece Meditations.

“When you first rise in the morning tell yourself: I will encounter busybodies, ingrates, egomaniacs, liars, the jealous, and cranks. They are all stricken with these afflictions because they don’t know the difference between good and evil. Because I have understood the beauty of good and the ugliness of evil, I know that these wrong-doers are still akin to me … and that none can do me harm, or implicate me in ugliness — nor can I be angry at my relatives or hate them. For we are made for cooperation.”

16) Self-reflection

Earlier in the post I mentioned Dr. Jordan B. Peterson’s self-development writing program Self Authoring. The program has you analyze your past, future, faults, and virtues. The program has been one of the most powerful exercises in self-reflection I’ve ever carried out.

When you reflect on your own character and actions you will gain a greater sensitivity or mindfulness toward how you think and what triggers you into negative emotions. With daily self-reflection you will be able to slow down the process of events that lead to unwholesome states and prevent them from throwing you into a cauldron of toxicity.

Seneca explains the power of self-reflection:

All our senses should be trained to acquire strength; they are by nature capable of endurance, provided that the mind, which should be called daily to account for itself, does not persist in undermining them. This was the habit of Sextius, so that at the day’s end, when he had retired to his nightly rest, he questioned his mind: ‘What bad habit have you put right today? Which fault did you take a stand against? In what respect are you better?’ Anger will abate and become more controlled when it knows it must come before a judge each day. Is anything more admirable than this custom of examining the whole day? How sound the sleep that follows such self-appraisal, how peaceful, how deep and free, when the mind has either praised or taken itself to task, and this secret investigator and critic of itself has made judgement of its own character! This is a privilege I take advantage of, and every day I plead my case before myself as judge. When the lamp has been removed from my sight, and my wife, no stranger now to my habit, has fallen silent, I examine the whole of my day and retrace my actions and words; I hide nothing from myself, pass over nothing. For why should I be afraid of any of my mistakes, when I can say: ‘Beware of doing that again, and this time I pardon you. In that discussion you spoke too aggressively: do not, after this, clash with people of no experience; those who have never learned make unwilling pupils. You were more outspoken in criticizing that man than you should have been, and so you offended, rather than improved him: in the future have regard not only for the truth of what you say but for the question whether the man you are addressing can accept the truth: a good man welcomes criticism, but the worse a man is, the fiercer his resentment of the person correcting him’?

The stoics were prolific journals. If there is one stoic practice I would recommend, it would be a daily journalling habit. I recommend you start with Self Authoring to cultivate the habit, but alongside that you ask yourself the following questions each night and note your thoughts.

Three questions to ask yourself each evening:

- What bad habit have you put right today?

- Which fault did you take a stand against?

- In what respect are you better?

How to Control Anger In a Nutshell

1) Recognize that anger is awful

Anger is bad news. Only in extremely rare cases can you justify bad bouts of anger. Anger is contagious, incredibly hard to manage, and controls you.

2) Make the attainment of a tranquil mind your biggest goal

The stoics put equanimity as their highest goal. To them there was nothing more important than being calm and tranquil and undisturbed. Anger is the most disturbing emotion.

3) Choose your friends wisely

If you are prone to anger, do not choose friends that trigger than anger or provoke you with teasing.

4) If you have a hot temper, use art and music to ease the mind

Art, music, movies stimulate and calm the mind. Keep a relaxing playlist at hand for when you get stressed.

5) Learn your anger triggers and stop it early

Practice meditation and mindfulness to gain a deeper moment-by-moment understand of your mind. Learn what makes you tick and what propels you to anger. Then stop it early.

6) Resist the impulse to be curious

Don’t be curious about things you know will disturb your tranquility unless you consider it vital to know. Most of the time we seek to find out what someone said about us, the information doesn’t do us much good.

7) Don’t seek reasons to be angry

When you find yourself getting frustrated, don’t look for more reasons to be angry. Your mind will be geared toward finding things to take offense over. Instead, resist this impulse and focus on thing that will lead to calm.

8) See yourself in the offender

You have acted terribly many times in the past. Remember that the person who has offended you is human just like you. You are more similar than you are different.

9) Just wait

The best advice is also the most cliche advice. When you feel angry, do not act out. Just wait. Count to ten. Just wait until it subsides. This will nearly always be something you’ll be glad you did.

10) Do battle with yourself

When you feel angry, challenge your own thoughts and assumption. Hold firm, do not give in. Let your rational self fight your primal self. Self-battle is the source of self-mastery.

11) Build a collection of anger case-studies

Keep a mental or physical note of good and bad examples of anger control. Have a few examples in your mind of ways anger has caused lots of harm, but also have examples where people have dealt with their anger in noble ways.

12) Develop tolerance

Becoming more tolerant and accepting of bad behavior is an important stoic virtue. This doesn’t mean that you become a pushover. It just means that you don’t allow everything and everyone to trigger you into anger and self-destruction.

13) Heal rather than punish

Focus on rehabilitating people who act wrongly rather than hurting them. This puts you into a position of power and will also allow you to maintain integrity.

14) Turn anger into appreciation

The antidote to anger is gratitude. In every hot situation where anger has the potential to arise, there is likely something that will teach you a lesson or help you grow.

15) Stop being a diva

Cultivate your inner warrior. Stop depending on luxury and comfort for your wellbeing. Take insults and grievances as training in the school of life. Do not throw your toys out of the pram whenever things don’t go your way.

16) Self-reflection

Keep a journal. Reflect daily on your habits, virtues, and faults. Learn what makes you tick and set daily goals to become the vest version of yourself.

Jon Brooks

Jon Brooks is a Stoicism teacher and, crucially, practitioner. His Stoic meditations have accumulated thousands of listens, and he has created his own Stoic training program for modern-day Stoics.