Jon Brooks • • 17 min read

Traumatized Supermen: The Self-Improvement Industry’s Most Destructive Blindspot

When you think of an addict with psychological trauma, what image comes to mind?

Here’s what our collective unconscious a.k.a. Google image search brings up:

What do we see?

Pale, grey, sick people who are using hard drugs.

They look extremely unemployable and poor.

But is this really what an addict looks like?

Sometimes, sadly, yes.

But addicts can also look more like this:

“But so what? Sometimes, celebrities get rich and stressed and unwind with sex and drugs… it’s part of the lifestyle.”

Well… maybe…

But I don’t think that really captures what’s going on here. These are not just celebrities, are they?

They are some of the most talented actors, musicians, comedians, and athletes of all time.

They are extreme high achievers, and they are also addicts.

At this point it might be good to give an actual definition of the word “addiction.”

Dr. Gabor Maté defines addiction as follows:

An addiction is any behavior, substance related or not, that an individual pursues because they find pleasure, relief, or they crave it temporarily, so they pursue the pleasure and relief despite negative consequences. And they don’t give it up, in the face of negative consequences. I said any behavior. So that could be sex, gambling, eating, shopping, work, relationships, or substances.

If this doesn’t quite hammer the point home, let me go a little bit further.

Review the following list:

- Oscar Wilde died at the age of 46 from meningitis or syphilis. In the last years of his life he spent most of the money he could find on alcohol.

- Jimi Hendrix died at the age of 27 from choking on his own vomit, while intoxicated on barbiturates.

- Steve Jobs died at the age of 56 after battling Pancreatic cancer for a decade. He was known to constantly experiment with extreme eating plans such as the “apple-and-carrots-only” diet.

- Kurt Cobain died at the age of 27 from a self-inflicted shotgun wound to the head. He was addicted to heroin at the time.

- Virginia Woolf died at the age of 59 when she filled her overcoat with stones and walked into a lake.

- Ernest Hemingway loved alcohol and was rumored to drink a quart of whiskey a day later in life. He died through suicide.

- David Foster Wallace suffered from depression most of his adult life. He hung himself when he was 46.

- Marilyn Monroe died at the age of 36 from barbiturate overdose.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, due to chronic migraines, nausea, and convulsions frequently took opium. He had a mental breakdown when he was 44 and died when he was 55.

- Diego Maradona, from the mid-1980s until 2004, was addicted to cocaine.

- Elvis Presley died when he was 42. The lab report noted there were “fourteen drugs in Elvis’ system, ten in significant quantity.”

Again, these were not just talented people. These were the best of the best, and they all displayed behavior characteristic of an addict.

Now, this raises a lot more questions than it answers.

- What if there’s a link between mental illness and creativity?

- What if the pressure of superstardom causes mental illness and stress?

- What if drugs help artists to create better work?

- What if they were just following cultural norms?

While I’m almost certain there is a plethora of reasons that contributed to the demise of the legends listed above, Gabor Maté’s polarizing views on addiction suggest there is an overriding feature behind the behavior of all addicts:

The root of “addiction” is not weakness of character, an ethical lapse, but psychological trauma.

Maté elaborates:

Addiction is not a choice that anybody makes; it’s not a moral failure; it’s not an ethical lapse; it’s not a weakness of character; it’s not a failure of will, which is how our society depicts addiction. Nor is it an inherited brain disease, which is how our medical tendency is to see it. What it actually is: it’s a response to human suffering, and all these people that I worked with had been serially traumatized as children. All the women had been sexually abused. All the men had been traumatized, some of them sexually, physically, emotionally neglected. And not only is that my perspective, it’s also what the scientific and research literature show. So addiction then, rather than being a disease as such or a human choice, it’s an attempt to escape suffering temporarily.

Psychological trauma, and especially “childhood trauma,” has lost much of the psychological significance it once had. The psychoanalysts theorized deeply into the turbulent psyche of the child, but today talk of the Oedipal or castration complex seems not only archaic but also ludicrous.

Now we live in the age of neuroscience, positive psychology, biohacking, and supplement stacking. We have research in every direction telling us how we can be successful, get rid of bad habits, rewire our brains, supercharge our willpower, and be the superhuman we dreamed of becoming as children.

But psychological trauma is a very real thing, and it makes us sick—physically and mentally.

Clearly many of us display more addictive behaviors than we like to admit (caffeine, nicotine, pornography, eating, work, etc.), and thus according to Maté we have all been traumatized to greater or lesser degrees.

So the next logical question to ask, is “what is psychological trauma?”

On the extreme end, we think of the traumatized as army veterans or extremely disenfranchised children. But as Bessel van der Kolk writes in The Body Keeps the Score, his masterpiece on trauma:

One does not have to be a combat soldier, or visit a refugee camp in Syria or the Congo to encounter trauma. Trauma happens to us, our friends, our families, and our neighbors. Research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has shown that one in five Americans was sexually molested as a child; one in four was beaten by a parent to the point of a mark being left on their body; and one in three couples engages in physical violence. A quarter of us grew up with alcoholic relatives, and one out of eight witness their mother being beaten or hit.

If I were to ask you, “are you suffering with any of the residual effects of psychological trauma?”, could you answer confidently that you are not?

The reason why childhood trauma is particularly damaging and common is because children are like sponges, absorbing everything around them, trying to understand the meanings of things and the relationships between others and themselves. Gabor Maté writes:

When people are traumatized, a number of things happen. One is, they begin to feel themselves as deficient. Children are narcissistic, and I don’t mean that in the sense of a pejorative implication. What I mean by that is they think it’s all about them. They think everything is about themselves. When good things happen to a child, the child will assume, “Hey, I must be great because I’ve got all these great things happening.” But if bad things happen to a child, if the child is yelled at or beaten or sexually abused or told to go to their room when their parents don’t like their behavior, or the parents are just depressed or unhappy, or stressed—traumatized in their own life—the child thinks, “These bad things are happening because I’m a bad person.” So then you have low self-esteem.

Typically, the more adrenaline you secrete in a given situation, the more precise your memory of that situation will be. But this is true only up to a certain point. When confronted with “inescapable shock” or horror, the system becomes overwhelmed and breaks down.

The imprints of psychological traumatic experiences, then, are not neat coherent narratives that you can articulate: they are closer to raw sensations. Because traumatic memories are not fully integrated as a past experience, their existence creates a feeling of an ever-present threat. You become hyper-sensitive to any trigger which reminds you of your trauma.

This means that you may endlessly continue to “relive” your psychological trauma in the real world without consciously acknowledging the memory at its root.

Bessel van der Kolk provides the following example with one of his clients:

When Annie started to like me she began to look forward to our meetings, but she would arrive at my office in an intense panic. One day she had a flashback of feeling excited that her father was coming home soon—but later that evening he molested her. For the first time, she realized that her mind automatically associated excitement about seeing someone she loved with the terror of being molested.

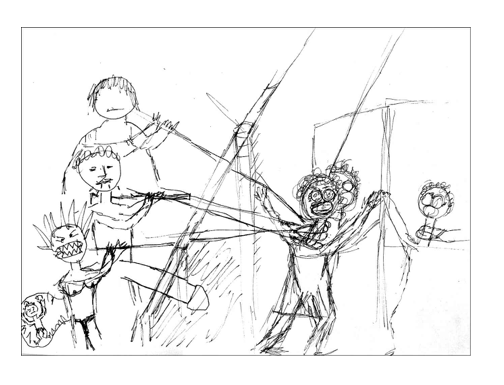

In another case, Bessel van der Kolk had a client called Marylin who had a history of self-harm and violent outbursts but reported a happy childhood. When she drew this image of her family in one of her sessions, Kolk knew he had to tread lightly.

After a year of therapy, she finally contemplated the idea that she may have been abused as a child. Kolk writes:

Her immune system, her muscles, and her fear system all had kept the score, but her conscious mind lacked a story that could communicate the experience. She reenacted her trauma in her life, but she had no narrative to refer to.

Before you start getting paranoid that you have hidden memories, stories like this are rare and emerge when there is a significant incongruence between one’s behavior and one’s history. The point is that traumatic memories are stored different from normal memories.

How Are We Coping With Psychological Trauma?

The Buddha said, “Life is suffering.” But a closer translation of his original quote is “Life is unsatisfactoriness.”

According to the Buddhist doctrine we spend our lives in three primary and overlapping states of consciousness:

- Grasping: When we like something, we want to cling to it and consume more.

- Aversion: When we don’t like something, we push it away.

- Boredom: When we are bored or overwhelmed we like to “zone out” and distract ourselves.

All of these states are life-denying and only increase unsatisfactoriness. Grasping onto things is futile, because nothing is permanent; avoiding things makes us weaker and increases suffering at a later date; boredom is by definition being discontent with where you are.

We all shuffle between these modes of being, but the traumatized individual, with their increased sense of lack and pain will enter these states with more ferocity. They will grasp onto any activity that reduces their turmoil, avoid anything that reminds them of their nightmares, and try to distract themselves as much as possible to avoid confronting the storm of life.

These behaviors are not a sign of weakness. In fact, these behaviors help them survive in unimaginable circumstances. Every story of psychological trauma is an incredible story of survival and strength.

Addictions make life bearable. When you get high on your elixir of choice, things are just fine. How you look, your circumstances, and relationships seem “just right.” There is no unsatisfactoriness when one is high. The unsatisfactoriness comes later. When one has withdrawal from drugs, grasping, aversion, and boredom become demons in the mind that in many unfortunate cases consume their host.

Some cope with their psychological trauma in less overtly self-sabotaging ways. Maté refers to these as “respectable addictions.” One predominant respectable addiction, I believe, is the drive to self-enhance.

Self-Enhancement as Symptom Control

Earlier I made a list of world class performers who were plagued with addictions. According to Gabor Maté, since these people displayed addictive behavior they almost certainly had unresolved traumas beneath the surface. The question then becomes, how did these individuals become so successful even though they were traumatized? Isn’t trauma meant to disable us and stifle our climb out of despair?

Psychological trauma effects people in different ways. Sometimes trauma can be so devastating, one never has even the chance of recovery. The trauma strips them of their ability to learn and improve and communicate and elevate themselves at all. For others, psychological trauma can provide profound motivation to move away and rise up from the situation that created it. The word “enhance” can also be defined as “to raise up.” And many people turn to self-enhancement as a means to deal with trauma.

Michelangelo is a great example of this. When he was seventeen, he was punched in the nose by a fellow student. After the attack, Michelangelo was left with a disfigured “boxer’s nose” for the rest of his life. One day his face changed for the worst, permanently. Being young, insecure, and highly-sensitive to beauty, this event was nothing short of traumatic for the art student. Many historians believe that Michelangelo’s low opinion of his own appearance after this event pushed him to relentlessly create perfect human specimens in his work.

Self-enhancement can certainly be an aid to recovery, in that it may help you stay on track and manage the otherwise unmanageable parts of your existence. Setting goals to create an appealing future, becoming fitter, eating a good diet, building skills, surrounding yourself with positive people, and scheduling your time can absolutely reduce the symptoms of psychological trauma.

But does symptom control actually heal psychological trauma?

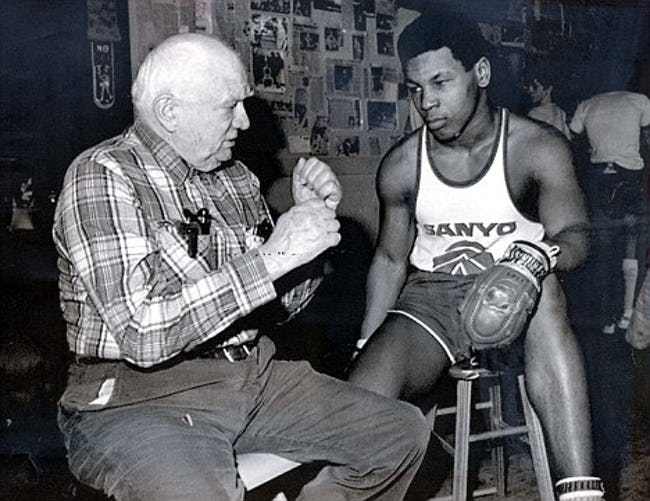

Mike Tyson: From Street Urchin to Boxing Superstar

I read Mike Tyson’s amazing autobiography last year, and found out that he had quite a life. When Tyson was ten, he was forced to move to Brownsville, Brooklyn, New York City. He describes the atmosphere:

You could totally feel the difference. The people were louder, more aggressive. It was a very horrific, tough, and gruesome kind of place. My mother wasn’t used to hanging around those particular types of aggressive black people and she appeared to be intimidated, and so were my brother and sister and me. Everything was hostile, there was never a subtle moment there. Cops were always driving by with their sirens on; ambulances always coming to pick up somebody; guns always going off, people getting stabbed, windows being broken. One day my brother and I even got robbed right in front of our apartment building. We used to watch these guys shooting it out with one another. It was like something out of an old Edward G. Robinson movie. We would watch and say, “Wow, this is happening in real life.”

Tyson had an absent father, a prostitute mother, and lived in an extremely violent neighborhood. He soon became a thief and a street fighter, taking on opponents much bigger and older than he was. By the time Tyson turned thirteen he had been arrested thirty-eight times. It was when he was sent to a young offenders’ school, he met Cus D’Amato—a legendary boxing trainer who saw potential in Mike.

Tyson soon moved into the same house as Cus, and dedicated his entire life to becoming a world champion heavyweight boxer. During the 7 years Tyson worked with Cus D’Amato, he didn’t cause any more trouble. He didn’t take drugs. He didn’t have girlfriends. He had his goal to be the best boxer in the world and nothing distracted him.

Tyson’s daily routine was something like the following:

4am.: Wake. Jog 3-5 miles.

6am: Shower. Go back to bed.

10am: Eat breakfast (Oatmeal with fruit, OJ, and vitamins, washed down with a protein shake.)

12pm: 10 x rounds of sparring. 3 x sets of calisthenics.

2pm: Eat lunch.

3pm: 4-6 rounds of sparring, bag work, slip bag, jump rope, Willie bag, focus mitts, and speed bag. 60 minutes on the stationary bike. 3 x sets of calisthenics.

5pm: 4 x sets of calisthenics. Slow shadow boxing.

7pm: Eat dinner.

8pm: 30 minutes on the exercise bike for recovery purposes only.

9pm: Study fight films or read. Sleep.

Tyson became rich, powerful, intimidating, disciplined, famous, and the youngest heavyweight world champion of all time. He had enhanced himself to superhuman status, but he was still a traumatized superman.

After Cus D’Amato died, Tyson’s demons began to surface. Tyson no longer had a father figure imposing a regime of self-enhancement upon him, and his symptoms of psychological trauma broke free from the shackles of routine.

Tyson started using drugs and prostitutes to a rather extreme extent. “I know there’s an empty hole in me,” Tyson later said, “and I spent a lot of years trying to fill it with drugs and booze and sex.”

Mike Tyson’s estimated net worth at the height of his career was $300 million, but in 2010 on The View he told the hosts, “I’m totally destitute and broke.”

You can only run from psychological trauma for so long. Eventually, you have to turn around and face it fully. Otherwise, it will take you from behind.

How Can We “Process” Psychological Trauma?

Clearly money, fame, success, popularity, or talent alone does not help us to reliably escape the grasp of psychological trauma. Self-enhancement and self-healing are two different things.

The old English version of “heal” was hǣlan. This simply meant “restore to sound health.” When one is sick, one does not focus on goal-setting or running a marathon or becoming a world champion boxer. One focuses on getting healthy again. This is the fundamental difference between enhancement (to raise up) and healing (to restore back to health).

Healing typically goes on deep within and its fruits are often invisible and unimpressive to those who have not gone through a similar process, and healing is all about “the process.”

Jordan Peterson provides a great overview of what psychological trauma is and how to process it in his interview with Stephen Molyneux:

Let’s define what processing means. Let’s say you had a pretty painful history of being bullied when you were thirteen. And you’re still carrying that with you. You’re carrying that with you in your posture. You carry it with you in your assumptions about people. This is all implicit, right. It’s not explicit. You carry it with you in the form of resentment and questions about what might have been. And you carry it with you because you’ve been demeaned by it. But you know, you’re not thirteen anymore. You’re forty. And those experiences are not transferable in any simple manner to your current reality. So you go back and you think, “What happened? What exactly happened?” And what “what happened” means is, what were the causal pathways that put me in that position of vulnerability and inferiority. And you want to specify them as carefully as possible because what the part of you that’s hanging on to that wants to know is, “Have you changed enough so that won’t happen again?” And if the answer to that is “yes”—even through thinking—then you realize “well I’m not that person anymore. Or you go back to the experience and you figure out, “This is what I did and I could stop doing that.” Then the icy hands of that traumatic experience will release; you will be released from it. Because what your mind wants to know—your unconscious mind let’s say—is, “Have you resolved this issue to the degree that it is unlikely that it will occur again?” That’s what it means to have processed it.

Jordan Peterson is saying that we must physically learn that the threat your body thinks is present, has gone—that you are not the same person living in the same epoch as when the threat originally occurred. One might think upon reading this that in order to overcome trauma we need to become physically stronger or increase our status. But as we’ve seen in Mike Tyson, his physical image did not match his emotional one.

I once watched a fantastic short documentary made by Vice called Britains Toughest Debt Collector, in which we meet a man who has been in and out of psychiatric hospitals due to extreme self-harm, suicide attempts, and drug use. He lifts up his top to show us a very deep gash in his stomach that has fresh blood. The man is a talented boxer and all-round tough guy. He reveals in an interview, however, that he was repeatedly raped when he was twelve by an older boy in a foster home. Now he acts violently and imagines the rapist as a way to soothe his pain. The man is tough, a good fighter, but a broken weak child inside.

When you heal from psychological trauma it is important that you do aim to become stronger, but not just physically stronger—to goal is to become wiser, more astute, less naive, more confident, more emotionally balanced, and more articulate and to feel as though you’ve gained some mastery over the past.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to elaborate on all the different ways one can process psychological trauma. If you would like to get an extensive rundown of the ways you can heal trauma, I encourage you to read the book The Body Keeps the Score. It is one of the most readable and comprehensive books on trauma out there. After reading the book you will know exactly how psychological trauma works and exactly how to heal it so you can start living a flourishing life. You can also watch Kolk’s lectures on Youtube for free—this video is a great overview of his ideas (the first five minutes are gold).

That said, there is one particularly powerful intervention I will touch on that I feel qualified to discuss.

Self Authoring Your Past

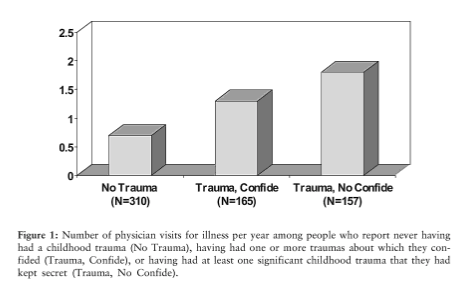

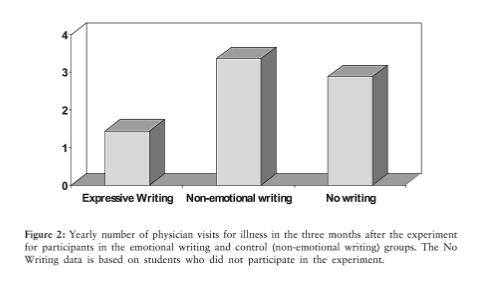

James W. Pennebaker is an American social psychologist who has done a lot of work on the healing power of expressive writing, or as Dr. Jordan B. Peterson calls it, self authoring.

Pennebaker explains the therapeutic effects of self authoring in his book, Words That Heal:

What is the best way to get over a psychological trauma? Over the last century researchers have been tackling this problem in many ways with varying success. For example, in-depth psychotherapy and medication have helped millions of people. Relaxation techniques including yoga and meditation have also proved beneficial. Strenuous exercise and improved eating habits can also help. Some of these strategies work for some people some of the time.

The reality, however, is that there is no one technique that is guaranteed to work. Since the mid-1980s, an increasing number of studies have focused on the value of expressive writing as a way to bring about healing. The evidence is mounting that the act of writing about traumatic experience for as little as fifteen or twenty minutes a day for three or four days can produce measurable changes in physical and mental health. Emotional writing also can affect people’s sleep habits, work efficiency, and how they connect to others. Indeed, when we put our traumatic experiences into words, we tend to become less concerned with the emotional events that have been weighing us down.

Simply self authoring for 15 minutes in private about traumatic experiences a few times can have permanent changes on your emotional and physical health. Understanding and writing clearly about the events that caused your traumatic experiences—the story of your psychological trauma—allows your mind and body to process those memories anew, in a healthy way, and let go of the past.

Jordan Peterson actually created a very affordable yet life-changing self-developing writing program aptly called Self Authoring. In the program, he has you divide your life into different sections and write an autobiography. There is also a section where he has you dissect your current faults and virtues, and also a section dedicated to the future to help you develop a compelling plan that you can actually achieve. Peterson based this program on the work of Pennebaker.

I’ve been working with Self Authoring for the last few months and have found it to be one of the most healing and meaningful experiences of my life. I see my past in a completely different way, am less neurotic and nihilistic, more motivated, and all around a stronger force in this world. After breaking down and self authoring my past in detail, I was able to see the connections between my own addictions and psychological trauma, and found it much easier to let them go—I thought they were my personality, but they were actually my coping mechanisms.

Conclusion

In the USA alone, we spend 11 billion dollars each year on self-help books. Clearly the desire to enhance ourselves is stronger than ever. Self-enhancement apps are some of the most popular apps in the world. The popularity of fitness is at an all time high too. And if this reduces suffering in the world, this is only a good thing.

Healing, however, is very rarely discussed in the self-improvement world. Instead, this task is left for fringe spiritual circles and is often portrayed as soft and woo-woo.

I hope that I have showed you in this article that self-enhancement without the inclusion of self-healing will likely create traumatized supermen—dazzling but unstable stars that eventually collapse in on themselves.

We do not have to feel miserable and empty to be great. We do not have to be highly successful to feel whole. We just need the courage and calm, to respectfully let go of the past so we can live right now.

Jon Brooks

Jon Brooks is a Stoicism teacher and, crucially, practitioner. His Stoic meditations have accumulated thousands of listens, and he has created his own Stoic training program for modern-day Stoics.