Jordan Bates • • 7 min read

Transcending Tribalism: Jonathan Haidt on How to Escape the Political Matrix

“Why are THOSE PEOPLE so awful?”

As politics in the US becomes increasingly polarized, more people than ever seem to be asking this question.

Many people on both sides of the political spectrum are quick to attack and dismiss those on the opposite side. Few people, however, make an effort to step back from the madness and ask, “What’s really going on here? Why are these otherwise good people fighting so viciously? Why does politics seem to make everyone crazy?”

These are precisely the sort of questions that the moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt tries to answer. In the duration of this post, I’ll explain Haidt’s eye-opening conclusions about why good, well-intentioned people are divided by politics.

Whether you read the rest of the article or not, I highly recommend watching Haidt’s TED Talk on “the moral roots of liberals and conservatives.” In this talk, Haidt basically explains why everything you think you know about politics is misguided and how to escape the “matrix” of endlessly divisive political discourse:

Tribalism: The Root of Political Craziness

In a recent essay, I argued that tribalism is to blame for much of the political insanity we’re seeing in 2016. Jonathan Haidt’s ideas/research support my hypothesis. My argument went something like this:

1. As humans, we evolved to form tribes.

2. We still form tribes of all sorts to this day.

3. This is often a good thing.

4. However, at extreme levels, tribalism becomes very bad.

5. When tribalism is ratcheted way up, people become convinced that their tribe is Absolutely Right and other tribes are wrong and evil; they become willing to do awful things they wouldn’t normally do to defend their tribe and denounce other tribes.

That’s Tribalism 101. Tribalism arguably underlies the majority of conflict and violence in human history, as well as the political hostility one witnesses nowadays in the US and elsewhere. In the case of the US, it seems that a rapidly changing economy, loss of trust in the Establishment, stark disagreement regarding political correctness, and polarizing media, among other things, are fanning the flames of tribalism, causing people to become exceptionally fierce in defense of the Red Team or Blue Team.

You probably know these guys. (Source)

“But wait, how do people end up on the Red Team and Blue Team? And why do these two main tribes disagree so violently about what should be done?”

That is a damn good question. And it’s the main subject of this post. Let’s get into it.

“But aren’t those other guys actually awful?”

No, most of them aren’t, actually. Believe it or not, most people are decent and well-intentioned and genuinely believe their political views uphold what is good and moral in the world.

The problem is that people don’t agree on what the words “good” and “moral” mean.

And here’s a strange thought: Maybe we wouldn’t actually want everyone to agree on what these words mean.

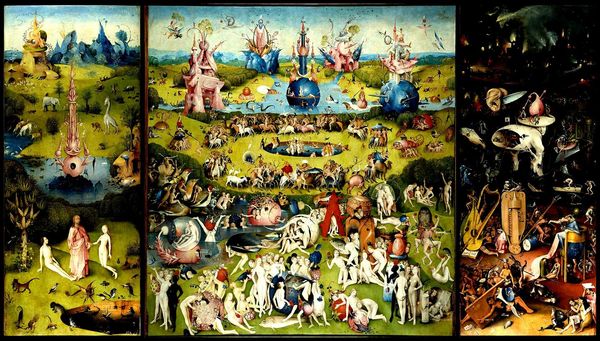

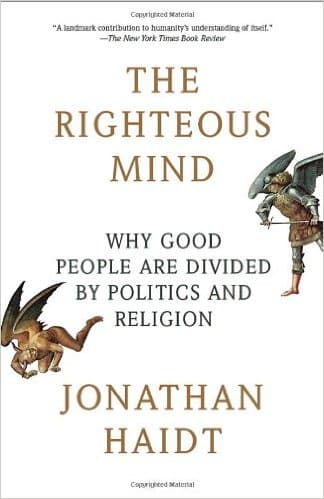

That last sentence is the hypothesis of Jonathan Haidt, the moral psychologist I mentioned earlier. Haidt helped to develop Moral Foundations Theory, which he outlines in a book I highly recommend: The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. You can read the book’s key insights for free on Blinkist, if you like.

In The Righteous Mind, drawing on 25 years of research in evolutionary psychology, social psychology, and anthropology, Haidt argues that:

- Human moral and ethical judgments are made on the basis of intuition much more than rationality.

- Our moral/ethical intuitions tend to be based on one or more “innate and universally available psychological systems”—i.e. systems for determining moral/ethical worth which are innate in all human minds.

- The five primary psychological systems—the five foundations of morality in human beings—are: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation.

- Each unique culture constructs “virtues, narratives, and institutions on top of these foundations, thereby creating the unique moralities we see around the world.”

Fascinatingly, Haidt’s research has shown that politically liberal people in the modern world heavily favor just two of the human moral foundations: care/harm and fairness/cheating. That is, liberals have elevated the virtues of caring and fairness above all else, to the point of almost entirely dismissing the value of loyalty, authority, and sanctity. Conservatives, on the other hand, tend to utilize all five of the moral foundations in approximately equal measures. This doesn’t mean conservative morality is better or more accurate than liberal morality—just different.

Haidt suggests that most modern political disputes can be traced to the valuation or devaluation of loyalty, authority, and sanctity—the three moral foundations over which liberals and conservatives demonstrably disagree most violently.

And get this: Haidt’s research has shown that it’s possible to predict whether someone is liberal or conservative based on whether they have a high or low degree of openness to experience, one of the Big Five personality traits. Furthermore, openness to experience is believed to have a genetic component, meaning that a person’s level of openness may be largely determined before they are born. If you’ve jumped ahead in the line of reasoning, you’ve already realized the startling conclusion:

People’s political orientation may be largely predetermined before they’re born.

Haidt’s research on openness to experience isn’t the only research that has suggested this. A number of other studies have suggested a link between biology and political orientation.

“Dear God, but, but… that means those awful other guys might have just been… born that way!”

Indeed, that is the implication here.

“But, but… that means we’re probably never going to be able to get rid of them or convince them that they’re WRONG.”

Nope, probably not. However, all is not lost.

Escaping the Moral Matrix

Haidt points out that liberals and conservatives both have something valuable to offer in the ongoing development of our world. Liberals tend to undervalue the goodness of the order, stability, and prosperity we’ve already attained, in favor of focusing on possibilities for a much brighter, better future. Conservatives, on the other hand, tend to undervalue future possibilities, in favor of focusing on the goodness of what has already been attained. Liberals overlook the fact that there are more ways to break complex systems than improve them, while conservatives overlook the fact that over the long span of history, societal change has often (though certainly not always) been a force for tremendous good.

Haidt argues that these liberal and conservative biases—the liberal bias toward a Bright Future and the conservative bias toward a Beautiful Past—actually result in a kind of Yin and Yang dynamic. He suggests that the tension between liberal and conservative ideas is healthy and productive for societies, and that being able to see this fact is the way to escape the “moral matrix.” Here’s a quote from his TED Talk on “the moral roots of liberals and conservatives”:

“So once you see this—once you see that liberals and conservatives both have something to contribute; that they form a balance on change versus stability—then I think the way is open to step outside the moral matrix. This is the great insight that all the Asian religions have attained. Think about Yin and Yang. Yin and Yang aren’t enemies. Yin and Yang don’t hate each other. Yin and Yang are both necessary—like night and day—for the functioning of the world.”

Or, as one of a rare breed of Actually Insightful YouTube Commenters put it:

“Liberals are there to liberate a culture from ideas and norms that have become outdated and counterproductive.

Conservatives are there to conserve the foundations and the stabilizing values of a culture.

We need both.”

Though I’m skeptical of whether this balance of political ideas is anywhere near Cosmically Perfect (as the Yin and Yang metaphor would suggest), Haidt’s argument is an interesting one and has merit. If nothing else, his research suggests that there are legitimate (and perhaps biological) reasons why all of us believe what we believe, that liberals and conservatives both serve important societal functions, and that we’re much better off attempting to understand others’ viewpoints, rather than demonize them. This effort to understand must, of course, also encompass the countless rich viewpoints that can’t be neatly categorized within the liberal-conservative dichotomy that defines so much of our public dialogue.

[David Wong’s recent deconstruction of the rise of Donald Trump over at Cracked.com is one of the greatest individual efforts to understand “the other guys” I’ve seen in recent memory, if you’d like to see an example of what the process of understanding looks like. This essay is another excellent analysis of a number of the forces/trends in America that are driving support of Trump.]

In today’s political climate, Jonathan Haidt’s ideas seem exceedingly important and necessary. The sooner we can cease engaging in tribalistic warfare, transcend the “moral matrix,” and recognize that both liberal and conservative ideas can have merit, the sooner we can engage in more productive political discourse and focus on addressing the most pressing global issues of our time.

More Resources

- Again, I highly recommend reading Haidt’s book, The Righteous Mind. You can grab it on Amazon or read the key insights for free on Blinkist.

- You can read Chapter 7 of The Righteous Mind—the chapter on Moral Foundations theory—for free online here.

- Here’s a great interview Jonathan Haidt did with Bill Moyers that makes a great follow-up to his TED Talk

If you’d like to deepen your compassion for those you disagree with while increasing self-awareness and overcoming destructive habits…

Our new course was designed for you.

Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a lover of God, father, leadership coach, heart healer, writer, artist, and long-time co-creator of HighExistence. — www.jordanbates.life