Jordan Bates • • 17 min read

How to Let Go of Dark Thoughts Like a Zen Master

What if I told you that one of the most life-changing realizations I ever had was that my thoughts aren’t that big of a deal?

You could be forgiven for assuming I was a little kooky.

But I’m totally serious. And (hopefully) not a kook. Let me explain.

Identity and Intrusive Thoughts

Most of us in the West identify very heavily with our minds.

When thoughts pass through our heads, we implicitly assume, “These are my thoughts. I am generating these thoughts.”

We take for granted that thoughts are like little ephemeral expressions of our deep essence.

But what happens when we have random thoughts that are dark, violent, or unsettling?

How do we reconcile our understanding of thought as self-expression with the fact that our minds sometimes generate really fucked up images and ideas?

That is a million-dollar question and one that tormented me for quite a long time.

About 6 years ago, while in university, I started having many intrusive thoughts. If you don’t know about intrusive thoughts, they’re basically involuntary troubling thoughts and images that pop into your mind without warning. According to Wikipedia:

“Many people experience the type of bad or unwanted thoughts that people with more troubling intrusive thoughts have, but most people can dismiss these thoughts. For most people, intrusive thoughts are a “fleeting annoyance”. Psychologist Stanley Rachman presented a questionnaire to healthy college students and found that virtually all said they had these thoughts from time to time, including thoughts of sexual violence, sexual punishment, “unnatural” sex acts, painful sexual practices, blasphemous or obscene images, thoughts of harming elderly people or someone close to them, violence against animals or towards children, and impulsive or abusive outbursts or utterances. Such bad thoughts are universal among humans, and have “almost certainly always been a part of the human condition.””

So the current scientific consensus is that most, if not all, people experience intrusive thoughts intermittently. Back in university, I didn’t know this, so I just thought I was mentally ill or something. One of the most common intrusive thoughts I would experience, while driving, was the realization of how potentially close I was to death, accompanied by an image of myself slightly pulling the steering wheel and causing a fatal car accident.

It wasn’t until a while later that I found out about the concept of “intrusive thoughts” and learned that it’s perfectly normal for humans to experience these. Although learning this brought a substantial amount of relief, I still had a hard time letting go of these thoughts. Sometimes I still do. Some thoughts are just so troubling that it feels like, “This has to say something shitty about me. This has to mean that there is something wrong with me.”

For those reading this and nodding along, I feel for you. I sincerely do. Intrusive thoughts fucking suck. And as the Wikipedia article says, while most people are able to just kind of brush off these thoughts, other people aren’t so lucky. For some, intrusive thoughts hold this extra fascination or sense of significance, and it’s really hard not to obsess about them and wonder they mean. Unfortunately, I think I’m one of the latter types, though I’m sure my case isn’t nearly as severe as some.

Lo! A Silver Lining

But, there’s actually a silver lining here, I think. Though highly unpleasant, intrusive thoughts can actually function as teachers. Or perhaps more aptly, they can serve as proverbial wily Zen masters who smack you over the head with a stick when you fuck up.

My problem with intrusive thoughts basically forced me to learn how to let go of thoughts and not identify so completely with my own mind.

Now, I’m going to tell you two stories that aren’t really stories, both of which will prove useful.

A Buddhist Story of Why Your Thoughts Aren’t That Big of a Deal

In Buddhism and other Indian epistemologies, the mind is considered a sensory organ, like the eyes or ears. In this conception, thoughts and other “mental objects” are considered akin to tastes and sounds. That is, they’re considered impersonal sensory phenomena that simply arise and fade within the field of consciousness, like a crow’s caw or the smell of a lilac bush.

In this formulation, having a disturbing intrusive thought is kind of like smelling old sushi: the experience is repellent, but one doesn’t assume it says anything fundamental about one’s identity. One just notices it, lets it pass, and moves on with one’s life.

One reason this attitude makes sense within the context of Buddhism is that Buddhists teach and cultivate something called non-dual awareness. Non-dual awareness refers to an awareness that transcends firm distinctions between oneself and the rest of existence. In a state of non-dual awareness, one understands that one is inseparable from the entire process of reality. That is, one’s seemingly individual being is akin to a single wave atop an ocean. The wave may have its own distinct properties, but it is also still clearly the ocean. It’s what the ocean is doing at the wave’s precise location. In some sense it is both itself and the ocean at the same time. The boundary between the two exists in some sense, but it’s nebulous, permeable.

Such is the case with human beings and the ocean of reality. We are our individual selves, but we are also continuous with the vast sea of subatomic particles that constitute everything in the known universe. And the boundary between the two is nebulous, porous. Understanding this, Buddhists see that selves are fuzzy and cannot be neatly defined; there is no objective boundary at which I end and the rest of reality begins.[1]

Furthermore, Buddhists espouse the doctrine of “no-self,” which states that living beings do not have any permanent, unchanging self, or essence. That is, selves are bundles of drives, ideas, experiences, bodies, and dreams, with nothing at the center holding it all together—no core thing to which everything is attached. The idea of a constant, unchanging “me” is seen as just another idea within the mind.

Interestingly, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, despite very limited contact with Buddhism in his lifetime, wrote of an idea that is eerily similar to the Buddhist idea of no-self:

“Main thought! The individual himself is a fallacy. Everything which happens in us is in itself something else which we do not know. ‘The individual’ is merely a sum of conscious feelings and judgments and misconceptions, a belief, a piece of the true life system or many pieces thought together and spun together, a ‘unity’, that doesn’t hold together. We are buds on a single tree—what do we know about what can become of us from the interests of the tree! But we have a consciousness as though we would and should be everything, a phantasy of ‘I’ and all ‘not I.’ Stop feeling oneself as this phantastic ego! Learn gradually to discard the supposed individual! Discover the fallacies of the ego! Recognize egoism as fallacy! The opposite is not to be understood as altruism! This would be love of other supposed individuals! No! Get beyond ‘myself’ and ‘yourself’! Experience cosmically!”

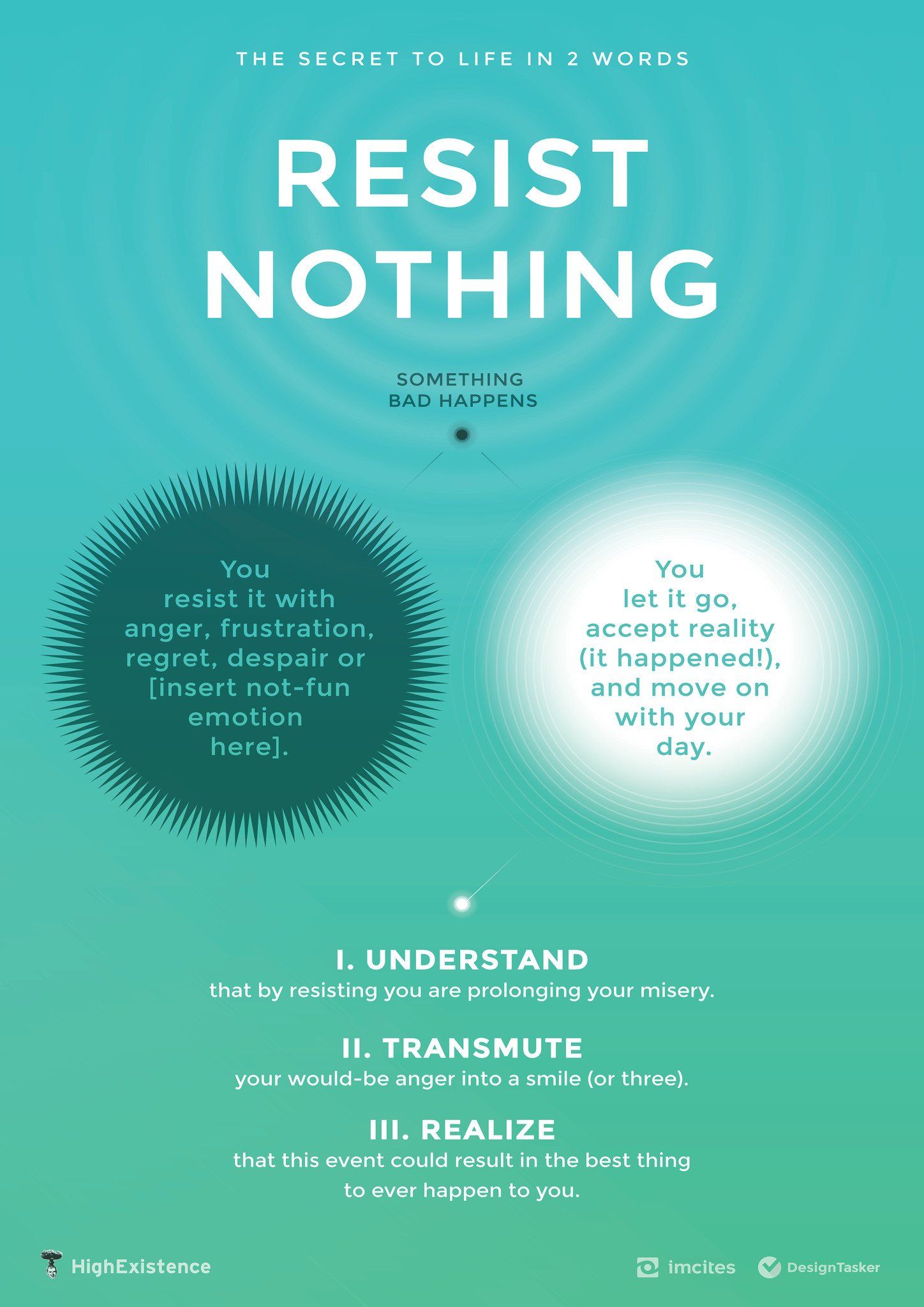

The process of liberation within Buddhism is largely a process of gradually embodying the truths of non-duality and no-self, while learning to let go of our individual preferences, desires, expectations, and attachments. Through this process, we come to participate more fully and compassionately in our world, let go of fear, and accept the endless ebb and flow of all things. We resist nothing.

The secret to life in two words.

Buddhists advocate for a specific technique for progressing along this path of realization. The way to liberation is to become an observer, a witness of your own mind. Instead of identifying with your passing stream of thought and sensation, you just watch it non-judgmentally and let it go. This is the essence of meditation: non-judgmental, accepting awareness of everything happening inside and outside of you in this present moment.

“You are the sky. Everything else – it’s just the weather.”

— Pema Chödrön

Non-judgmental observation allows one to step back from habitual over-identification with the personal self and occupy a more spacious awareness. In this awareness, the boundaries of the self become fuzzier, more porous, and the room one is occupying may feel as if it is as much a part of oneself as the passing thought that one has an upcoming dentist appointment. Everything becomes part of the same ambiguous dance of reality, and your role is simply to observe and accept the dance as it unfolds. Cultivating spaciousness allows one to become free from fixed interpretations and reactions, which are an enormous source of suffering.

That was a rather long-winded detour into the specifics of Buddhism, but hopefully you’re starting to see why Buddhists are able to not care so much about their thought content. Buddhists assert that upon close inspection, the self has no essential nature. Thus, there’s nothing for thoughts to be attached to. They don’t say anything about “you” in any deep sense because “you” do not exist in the way you think you do.

Furthermore, the boundary between the ever-changing you that does exist and the rest of reality is fuzzy and porous, so it isn’t entirely clear whether our thoughts should be considered things we generate, or things generated by a much more expansive process.

On a related note, it’s unclear how much of the content of your mind originated within you and how much originated elsewhere and found its way into your head. In fact, with the additional context of modern science, we can comfortably assert that most or all of what goes on in your head did, to some extent, originate outside of you, in the gene-sculpting process of evolution or in the natural and cultural environments in which you were raised.

As such, “your” thoughts are arguably as much the world’s thoughts as they are your own. What they reveal about you is thus quite limited, and much of what passes through your mind probably doesn’t say anything about Who You Really Are (whoever that is).

And even if your thoughts were entirely yours in some solid way, Buddhists would see no way forward other than acceptance. The Buddhist says, “If you can’t change it, resistance is futile.”

Largely because of my intolerable intrusive thoughts, I was forced to start looking for answers wherever I could find them. The perspectives of Buddhism, combined with the practice of non-judgmental awareness, have been something of a godsend for me. They’ve allowed me to look at thoughts that previously would have disturbed me and just kind of shrug and get on with my day.

Remind yourself to let go.

A Scientific and Psychotherapeutic Story of Why Your Thoughts Aren’t That Big of a Deal

Just in case the Buddhist story about why your thoughts aren’t that big of a deal wasn’t totally convincing, there’s another set of perspectives I should mention here.

You see, as much as I’ve found Buddhist perspectives and practices to be useful and liberating, I’ve never entirely bought into the idea of no-self, or the firm emphasis on letting go of all of one’s individual preferences, desires, attachments, and expectations.

I’m ultimately agnostic about whether my individual self has some kind of soul or essential nature. Intuitively I’ve always had a strong sense of an essential Jordan-ness within me that has remained the same throughout my life. And don’t get me wrong; I’ve changed a lot over the years, but there seems to be some kind of persistent spark of personality beneath it all.

Furthermore, I tend to think that the individual self is more important than Buddhism suggests. Though I’ve found immense value in learning to have far fewer expectations, preferences, desires, and attachments, I’m not particularly keen on letting all those things go.

In other words, giving fewer fucks has proven very useful, but I don’t want to give zero fucks. I want to reserve a precious few fucks for the things that really, really matter to me, like creating useful and/or beautiful things, improving the world, learning endlessly, doing fun shit, traveling the Earth, and having loving relationships. I cherish my unique individual personality and path, and this makes it difficult to go “all in” on Buddhist philosophy.

Perhaps you’re like me in this regard. Maybe you find Buddhism useful but don’t think it’s the end-all-be-all, or maybe you feel even less charitable toward it.

If that’s the case, all is not lost. There’s still good reason to care a lot less about the specific contents of your thoughts.

First of all, it’s worth repeating what I said a couple minutes ago:

“In fact, with the additional context of modern science, we can comfortably assert that most or all of what goes on in your head did, to some extent, originate outside of you, in the gene-sculpting process of evolution or in the natural and cultural environments in which you were raised.”

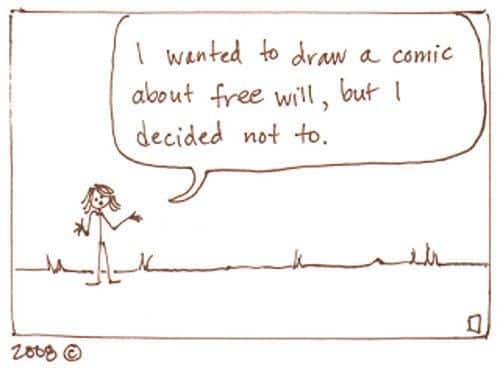

This notion is closely related to the idea of determinism—i.e. the idea that we do not have free will, that everything that happens is pre-determined to unfold in the precise way that it does.

Now, I’m ultimately fairly agnostic about the free will vs determinism debate, and I live my life as if I have free will. However, I fully acknowledge that we don’t choose the basic building blocks of our personalities; those are given to us by our biology and by the natural and cultural environments in which we are raised.

And just as we don’t choose the core components of our personalities, we don’t usually choose the thoughts that enter our minds. Spend some time meditating, and you’ll quickly realize that the mind is like a geyser, regularly spraying out arbitrary thoughts whether one asks for them or not.

If most of our core personality and thought content are not chosen by us, but are assembled deterministically by processes beyond our control, it follows that we should not feel guilty about the fact that we experience certain involuntary unsightly thoughts. We didn’t have any say in the matter!

Furthermore, while I do tend to believe that most of my thoughts say something about what makes me tick, it’s likely that what they often indicate is just that I have some “legacy code” stuck in my brain somewhere that I should choose to override. That is, we should consider that much of our involuntary thought content probably reflects largely obsolete biological or cultural programs that have found their way into our minds, but which don’t really say anything deep or meaningful about us.

And in fact, a version of this latter idea is one of the core tenets of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)—perhaps the most effective psychotherapy devised to date. Since the 1980s, CBT has gradually replaced Freudian psychoanalysis as clinical psychologists’ primary tool for helping people deal with dark thoughts. And one of the key shifts that came with CBT was the idea that your thoughts didn’t necessarily have to mean anything deep about you. Sometimes thoughts were just thoughts, not a defining aspect of your core essence and not things which must be acted upon in any way.

Some psychotherapists and thinkers take this even further and suggest that our thoughts are “fluctuations” or “wavelets” of a vast ocean of consciousness beyond us—something akin to what Aldous Huxley called ‘Mind at Large.’ If there is some kind of super-consciousness that we’re all tapping into, perhaps we’re akin to antennae receiving thought-signals from a source external to us. I’m skeptical of this idea, but I nonetheless find it fascinating.

Given these various considerations, I can’t go all the way, as some do, and say, “You are not your thoughts.” I might amend that mantra to, “Thoughts aren’t such a big deal,” or, “You are much more than your thoughts.” I currently believe my thoughts do bear some relation to my machinery of self, but that that relationship is often unimportant and usually ambiguous. If I a random violent image flits through my mind, I don’t know precisely what that means. Perhaps it’s a remnant of an aggressive program in my brain that would have served Hunter-Gatherer Jordan quite well several thousand years ago, but which is no longer useful most of the time (though I might be glad it’s still there in the event of a dangerous situation). I could dwell on this thought and wonder why I’m such a bad, fucked up person, or I could just look at the thought, acknowledge it, choose not to act on it, shrug, and get on with my day.

It’s important to note here that, in my view, one should not entirely disown one’s thoughts and pretend that they’re not at all a part of one’s experience or of human nature in general. Carl Jung coined the term “shadow” to refer to the parts of our individual and collective identities that we reject and repress. In Buddhist terms, if you prefer, you can think of the shadow as parts of our individual and collective experience that we reject and repress. Either way, when totally denied and neglected, our shadows will tend to manifest in ugly ways, both individually and collectively. Thus it’s crucial to admit that we—and humanity in general—do indeed contain darkness, and to make a habit of acknowledging and accepting the darkness present in our own experience.

I think intrusive thoughts are often eruptions of the shadow into the conscious mind. Since the shadow is by definition a part of our experience we don’t want to look at, this explains why intrusive thoughts can be so tormenting. However, it’s crucial to remember that you did not choose your fundamental personality; you usually don’t choose which thoughts enter your mind; and thus you need not feel guilty about simple thoughts (or emotions), however dark. They’re still just thoughts, and though they may reflect unseemly parts of your experience and/or nature, you do not have to act on them. You should, however, accept that they are part of you, or at least part of your experience, and gradually integrate them, coming to see them as normal parts of you, or your experience. Intriguingly, befriending “the monster within” prevents the monster from lashing out unexpectedly and can even reroute its energies in a productive, creative direction. For more on this, see David Chapman’s incredible six-part guide to the shadow, which incorporates Jungian and Buddhist perspectives (Part I / Part II).

One major lesson here is that it seems much truer to say that you are your actions than to say that you are your thoughts or emotions. By and large, you don’t choose your internal experiences, but you do choose how to respond to them (hint: often the best response is to do nothing at all). It isn’t clear where exactly your thoughts come from, or what they mean, or whether they’re even really “yours,” but your actions have a much more definite source.

While thoughts emerge haphazardly and involuntarily, actions tend to flow forth from the reflective part of you that observes your thoughts, ponders incoming data, and decides what to do. Thus, your actions seem like a much more reliable indicator of who you are—and perhaps more importantly who you want to be—than your thoughts. One might even argue that a person who consistently acts with wisdom and compassion despite regularly dealing with dark intrusive thoughts is more ethical and heroic than someone with a mind full of rainbows and unicorns who acts in the same way.

Even then, though, no one acts perfectly all the time. We all slip up and make reactive, or unconscious, or intoxicated errors. The deck is stacked against us. And if the determinists are correct, we can’t even be held responsible for our actions. So even actions are not necessarily reliable indicators of Who You Are, though I’d argue they’re much better signals to go by than mere thoughts. When you do inevitably make mistakes, take a page from the Buddhist playbook: accept what happened. No amount of resistance or tantrum-throwing can change what you did. The morally pragmatic option is to simply forgive the version of you that made the error, and strive to do better in the future.

Let’s Recap

Okay, whew, that was a lot. Let’s pause and take a deep breath.

1…

2…

3…

4…

5…

So in this article I began with the claim that your thoughts aren’t that big of a deal.

I then offered you two stories—one from a Buddhist perspective and one from a scientific/psychotherapeutic perspective—to back up my claim.

To recap, here’s why you shouldn’t identify so strongly with your thoughts or take them all that seriously:

1) Many prominent Eastern thinkers, as well as entire cultures, and have considered the mind a sensory organ, like the ears, with thoughts being akin to birdsong or the sound of a passing train.

2) It isn’t clear that “you” have any core essence, so to say that thoughts are “yours” may not even make sense. If you lack an essential self, there would be no unchanging thing to which thoughts could belong.

3) The boundary between you and the rest of the world is nebulous and porous, so it isn’t clear whether it’s more accurate to say that you generate your thoughts, or that they’re generated by this reality, by nature itself.

4) With some scientific context, we can easily see that most of what goes on within us originated outside of us, in the process of evolution or in the natural and cultural environments in which we were raised.

5) Even if your thoughts are entirely yours in some solid way, there’s no way forward other than acceptance. If something can’t be changed, resistance solves nothing and only leads to suffering.

6) Most of our core personality and thought content are assembled deterministically by processes beyond our control, so there’s certainly no reason to feel guilty about the content of our thoughts.

7) Even if our thoughts do reveal something about us, it’s probably often just some obsolete biological or cultural program that found its way into our minds and doesn’t say anything deep or meaningful about us. We can just override these programs and let their corresponding thoughts go.

8) One of the core tenets of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is that sometimes thoughts are just thoughts and need not say anything significant about Who We Are. And we don’t have to act upon them.

9) Thoughts might even be manifestations of some kind of super-consciousness we’re all tapping into. We don’t ultimately know precisely where they come from.

10) It’s important not to entirely disown dark thoughts and pretend they’re not part of your experience. Doing so can result in a dense Jungian shadow that manifests in ugly, self-sabotaging ways. Accept and befriend the monster within in order to tame it and harness its power in a healthy way.

11) At the end of the day, regardless of what thoughts are, it’s how you respond to them that really matters. How you act reveals who you are. Though, remember: mistakes are inevitable, so please, practice self-compassion and self-forgiveness.

It is my sincere hope that these considerations can help you, like they helped me, to give far fewer fucks about the content of your thoughts.

Even if you’re skeptical of much of what I’ve said, I encourage you to simply practice being a witness to the events of your own mind. The Indian sage Nisargadatta once said:

“If you believe your thoughts, you will be disappointed. Be the witness of thoughts. Remain as the seer.”

Practice simply observing your mental phenomena with the detached curiosity of a marine biologist observing the ineffable dance of a school of clownfish. Cultivate the ability to simply chuckle at much of what your mind does and think, “Huh, well isn’t that interesting.” I’ve found that simply by experimenting with detachedly observing thoughts and taking them less seriously, one begins to change one’s relationship to them. One begins to see that they’re not that big of a deal.

This practice of non-judgmental observation, as I said earlier, is the essence of meditation. A thought arises, you notice it, accept that it’s there, let it go. If you’d like to build a long-lasting meditation practice and other life-enhancing habits, I recommend our course, 30 Challenges to Enlightenment.

Outro

Nowadays, intrusive thoughts rarely disturb me. It’s almost become a contest to see if my mind can throw anything at me that I can’t handle.

When a weird or dark thought comes up, I just kind of glance at it and nod, as if I’m walking past an affable stranger on the street.

I keep walking.

The thought fades from view.

And I get on with the business of living—lighter and freer than I used to be.

Footnotes:

[1] The Buddhist conception of non-duality should be distinguished from the Hindu conception. In Hinduism, non-duality refers to monism, or the belief that “all is one,” that all boundaries and distinctions are ultimately illusions. Monism can be contrasted with dualism, or the view that boundaries are absolute, and the universe is made up of neatly separate objects. Buddhist non-duality is often confused with monism in the West, but in fact the Buddhist viewpoint is non-dualist/non-monist: That is, boundaries do exist, but they are nebulous and porous. Everything bleeds into everything else.

Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a lover of God, father, leadership coach, heart healer, writer, artist, and long-time co-creator of HighExistence. — www.jordanbates.life