Alexander Blum • • 14 min read

A Jungian Guide to Authoritarianism

“Long before 1933 there was a smell of burning in the air, and people were passionately interested in discovering the locus of the fire and in tracking down the incendiary.”

– Carl Jung, 1945, After the Catastrophe

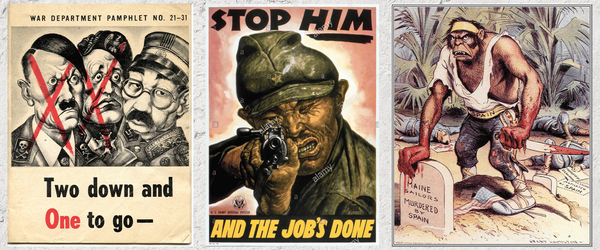

In our collective memory of twentieth century crimes against humanity, including the Soviet gulag, the extermination camps of Auschwitz and the picnic-and-a-photo nature of American lynchings, the common thread is that ordinarily civilians with no exceptional defects wound up being capable of malignant evil. Entire communities ignored the smoke of Jewish bodies meeting German skylines, and American schoolchildren stood beside burning black men on funeral pyres as they smiled and posed for photographs. Supposing that all people involved in such events were uniquely sociopathic would be convenient, but false. There is no evidence to suggest a fundamental change away from the human proclivity toward racism, nationalism and utopian violence since the early twentieth century. The difference between then and now is merely what culture permits; what illusions our neighbors allow.

The link between groups and their murderous behaviors was in some sense described best by the scholar Rene Girard. He conceptualized all group organization as centered around a ‘scapegoat’, a collective cause which a tribe could externalize their defects upon, like a twisted totem, and reject and publish that scapegoat in lieu of self-criticism. Girard found that only Christianity, of all the myths he studied, explicitly rejecting scapegoating in the figure of Christ, who was killed by the tribe and was fundamentally innocent.

Still, the problem of tribal behavior haunts all the world, especially what remains of the former-Christendom of Europe and North America. As Gandhi once said “I like your Christ, I do not like your Christians.” Lynchings and burnings-at-the-stake were features of the belief system which claimed the innocence of the scapegoat.

In 1957, the depth psychologist Carl Jung published The Undiscovered Self, a lengthily essay aimed at describing thedisenfranchisement of the human individual in the modern world, and the risks of technological and moral disaster that come from such individual powerlessness. Jung wrote: “The mass State has no intention of promoting mutual understanding and the relationship of man to man; it strives, rather, for atomization, for the psychic isolation of the individual. The more unrelated individuals are, the more consolidated the State becomes, and vice versa” (72). Since Jung’s time, states and corporations have grown into the same singular role – that of Hobbes’ all-consuming Leviathan, with private entities like Google, Amazon and Facebook constituting a public square far more closely than any state enterprise.

In retrospective, the cost of complex technological societies was always the diminution of the individual. In order to sustain a global network of mass trade and consumption, the individual had to offload many of its responsibilities and agencies onto impersonal third-party conglomerates. These entities – states and international corporations – can only exist insofar as individuals trade their freedoms away to those organizations capable of coordinating large-scale human behavior. No individual can build an iPhone, but a Leviathan – Apple empowered with corporate tax breaks and the bypassing of Western labor laws via trade agreements such as the TPP – can.

It is no surprise, either, that the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini arrived at a similar conclusion about the state of the individual in the modern world. Atomized people without beliefs are the most susceptible to fascistic ideology. Just last week, Republican congressman John Cornyn was blasted for tweeting a quote of Mussolini’s: “We were the first to assert that the more complicated the forms assumed by civilization, the more restricted the freedom of the individual must become.”

Mussolini, like most fascists, promises a form of catharsis in joining mass movements to oppose the alienation and atomization of individuals in the modern world. Jung noted that if individuals are unable to find any meaning in their own lives, and nowhere to assert their agency, dignity and individuation, they become susceptible to mass movements which uplift the State and the nation above the dignity of human life altogether.

Fascist scholar Julius Evola wrote Revolt Against the Modern Worldas a rallying cry for a return to a neo-traditionalist, patriarchal and feudal society with rigid and unbreakable class hierarchies, a State which paid fealty to the divine and rendered individuals irrelevant. If individualism has failed us, say the fascists, then we merely need a society where individuals are given their place at birth and have no mobility whatsoever. Fealty to the traditional divine image replaces individuality altogether.

For Jung, fascism is a threat precisely because the alienation, lack of individual achievement, loneliness and ‘atomization’ that characterizes modern life, especially in cities, is easily given over to what Jungians call the “mass man”. Mass man, distinguished from group-oriented man, is a force of nature, a crowd given over to the strongman or the ruling ideology with such fervor that individuals are no longer even present in the crowd. The solution to modern loneliness, for fascists, is to subordinate ordinary individuals to the “Great Individual”. In fascism, this phenomenon is obvious – see Hitler, Mussolini, and authoritarian revolutionaries like Vladimir Lenin. In smaller-scale cases, the crowd attending an American lynching is given over to the mass psychosis of white supremacy, which enabled self-identified Christians to observe individuals bound as corpses to trees and not recognize their own cross in the image.

The problem with complex global societies is that the human psyche did not evolve to exist in such an environment, and thus the psyche of the global citizen is uniquely vulnerable to mass authoritarian movements which exalt “nation and often race above the individual”. The promise of return to a group-oriented society, with thinking, feeling and community, is a powerful force. We do not relate intimately to insurance companies and the DMV, but they have replaced the interpersonal realities that once defined the human environment. The craving for a primordial world of glory, action, honor and violence, repressed in modern man, can be set free by historical circumstance such as perceived national shame or weakness.

Jung saw the inevitably of a “dictator State, since it is based on the greatest possible accumulation of depotentiated social units (74)”. This is why hard-right thinkers such as Mencius Moldbug advocate for monarchy and other extremely hierarchical forms of governance. As the Grand Inquisitor of Dostoevsky once argued, slavery to a system of hierarchy is preferable to Christ’s individuality, of consuming “locusts and roots” in the desert.

Of course, this is the illusion that history can be turned back in any meaningful way. All traditionalist critique of modernity seeks the return of an impossibility. In rolling back freedoms, in undoing the individual and restoring the primordial state of ur-consciousness, fascists and authoritarians are utopians in the backward direction of time.

Hannah Ardent and Umberto Eco, key anti-fascist thinkers of the twentieth century, saw the alienated middle class in particular as the most susceptible to fascism. The storms of the unconscious brew fantasies of ultimate catharsis and meaningful action. The frustrated middle class becomes a prime receptacle to become the “mass man” of dictatorial will.

Today, we see these impulses enacted in lone wolf scenarios. A mass shooter or a suicide bomber is often not a member of the oppressed class, but a spoiled member of the bourgeoisie. In his classic essay on the timeless characteristics of fascism, Eco writes: “Ur-Fascism derives from individual or social frustration. That is why one of the most typical features of the historical fascism was the appeal to a frustrated middle class, a class suffering from an economic crisis or feelings of political humiliation, and frightened by the pressure of lower social groups. In our time, when the old “proletarians” are becoming petty bourgeois (and the lumpen are largely excluded from the political scene), the fascism of tomorrow will find its audience in this new majority.”

The Western Psyche and the Cold War

Much of The Undiscovered Self is concerned with the effects of scientific rationalism and statistical thinking on individuals. Here, Eco and Jung part ways – Eco views attacks on science and rationalism as an element of fascism. While this is no doubt true, the reduction of human beings to statistical units contributes to the very powerlessness that propels fascistic thought.

Jung’s critique of statistical thinking demonstrates this. Taking the example of a bed of pebbles, Jung proposes that even if we know the average weight of a pebble in a pile is 145 kilograms, we still know nothing about any particular pebble in that pile. You might not find a single pebble that is exactly the average. This example is meant to indicate that any objective schema for understanding individuals tends to fall short in obvious ways. Averages are not souls. This also proposes problems for thinkers like Steven Pinker, who propose an analysis of upward statistical trends as reason not to feel pessimistic. No human in agony was ever permanently uplifted from that state by recognizing that poor people in 2019 at least have vaccines and microwaves.

Jung argues that two organizations have always sought to introduce scientific objectivity and regularity into individual life – the state and the church. We have already observed the influence of the modern state, but the church is in denial of the individual, for Jung, because it reduces the bizarre and unclassifiable life of an individual’s dreams, transcendental experiences and other unconscious realities into a set of incomprehensible and irrational “facts”, that is, the resurrection of Christ, baptism, and other matters of religious dogma.

The mysteries of being and faith became, in Christianity, just another set of objective facts, and the recognition of Christ and subservience to the church was offered as the path out of total chaos. And yet, any history of the twentieth century will clearly show that Western nations have become less religious and less dogmatic over time. I was never raised to attend church, for example, and The Bible is more a curiosity than a resource of endless certainty.

For this reason, Jung was pessimistic about the United States’ ability to combat the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Written in 1957, his political analysis is unmistakably of its time. Jung argued that neither the modern state nor the failing church were even remotely adequate to combat the religious fervor of the Soviet Union, which rejected religion and placed the state in its place. As much as Jung decried this form of organization, he admitted that it provided a far more powerful belief system than American corporate life, which is detached from the pretense of religious goals.

A religion will always defeat a secular belief system, argues Jung, because once religious aims and secular aims become identical, a total belief system is formed. Holding religion at arm’s length produces a fractured belief system, as is the case in secular American society, pretending that somehow Christ is present in the stock market.

The United States, an ostensibly secular society with a failing church, was able to attain a sense of unity only by focusing on a shared enemy. The Red Scare and McCarthyism were a form of religious crusade. Anti-communism was able to fill a particular void within the ordinary person and make an individual feel as if he were a part of something on the level of a theological battle. The presence of an all-consuming enemy prevented fatal self-reflection. The average American’s “spiritual and moral opponent…no longer dwells in his own breast but beyond the geographical line of division (59)”.

With the fall of the Soviet Union came the collapse of this scapegoat. Jung died long before that time, but following the arguments made inThe Undiscovered Self, the loss of the USSR as our collective ‘Great Satan’ means the loss of meaning for individuals who identified with their nation’s crusade against an enemy religion.

The social function of a foreign enemy is to “fascinate the outward eye and prevent it from looking at the individual life within (pg. 46)”. If the tide of crisis has turned within our borders, and the enemy is in fact not the Russian or the Muslim but ourselves, we have one last refuge to reject self-examination – “the normal individual…sees his shadow in his neighbor (pg. 46)”.

To prevent the dissolution of American society into neighbor vs neighbor, all against all, a new enemy needed to be created. This enemy came in the form of Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations. Rather than the religion of Stalin, the grand unifying theory of the American psyche became opposition to Islam.

After 9/11, the United States became a holy crusader. George W. Bush was able to call Islam a religion of peace, and simultaneously kill hundreds of thousands of innocent Muslims. But in the 2010s, this righteous butchering faded as the predominant character of American public life. Islam, contra Huntington, was not a sufficient foe to prevent the long-overdue self-reckoning of the fragmented American peoples.

The constant presence of an external enemy prevented American society from a fatal introspection. Among the repressed fatal flaws of Western culture, able to be ignored so long as we had a common external foe, was the inadequacy of our inherited Christianity, and the repression of our “crimes committed against the dark-skinned peoples during the process of colonization” (67).

Today, religious crisis and existential guilt about the past dominate the American mind. The 2010s have appeared as a kind of collective panic attack – all at once, our mass media seemed to collectively remember that our Founding Fathers owned slaves and that there was no real ‘purpose’ in life, and it has sent shockwaves of culture war, existential crisis, and a mood of nihilism into our society ever since.

It was an inevitable reckoning, and with no foe to oppose it, we are now left with internal contradictions. Neighbor against neighbor, and a rising tide of individual powerlessness that threatens to erupt in cathartic action. Political correctness, resurgent nationalism, and a mood of apocalyptic feeling toward technology characterize our era. The West no longer has a religion, and it seeks a new one. The trouble is, new religions always seem to disappoint. The neo-traditionalists emblematic of fascism therefore always remain at the gates – the foggy appeal of a return to less chaotic times will always retain power, and should the future become many times madder than it is today, these appeals will only gain in momentum and supposed credibility to the utopian dream of restoring “mass man”.

Jung in His Time, and Ours

The vacuum of meaning in an imperiled Western world is rapidly being filled in by strongmen. Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro has combined nostalgia for dictatorship with an anti-environmentalist, anti-gay politics, and has declared that the former dictatorship’s chief mistake “was to torture but not kill”. Former Trump strategist Steve Bannon has advised Bolsonaro as part of a “global populist movement”. Brexiteer Nigel Farage has called Hungary’s Viktor Orban “the future of Europe”. And in the United States, Donald Trump’s approval rating remains stable despite being credibly accused of criminal conduct on multiple fronts. At the same time, both Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel and Justin Trudeau of Canada face calls for resignation in the face of indictment and corruption.

Those who propose political centrism as an antidote to this phenomenon are humbled by the example of French president Emmanuel Macron, who despite beating the nationalism of Marine Le Pen in an election, boasts a “rising” 28% approval rating and faces the most massive ongoing protest movement in Europe by way of the Yellow Vests.

I confess my bias – I am a supporter of Bernie Sanders and believe that social democracy will do a great deal to heal the social fabric of the United States. Yet I cannot deny that this, like all political schemes, is a slow-moving state-driven enterprise without a personal component. It won’t heal our fractured communities and all non-economic anxieties, and the continued social frustration of the middle class will not be solved through purely economic solutions.

Perhaps the most radical aspect of Jung’s approach to fascism is that he is explicitly asking you, his reader, to conceive of yourself as a fascist. In your own heart you must see a monstrosity waiting to take your role in a group of crucifiers, and in this the whole secret of unconscious evil comes undone and blossoms into an undeniable facet of our internal nature.

The key to understanding Jung is that, contrary to the rationalistic psychology of today, he emphasized the non-rational experiences of dreams, spontaneous mental images, fantasies and other objective inner events that are not generated on purpose by the active conscious mind, but that impact our psyche without any agency from our consciousness at all. For Jung, “the unconscious is objective, manifesting itself mainly in the form of contrary feelings, fantasies, emotions, impulses and dreams, none of which one makes oneself” (61).

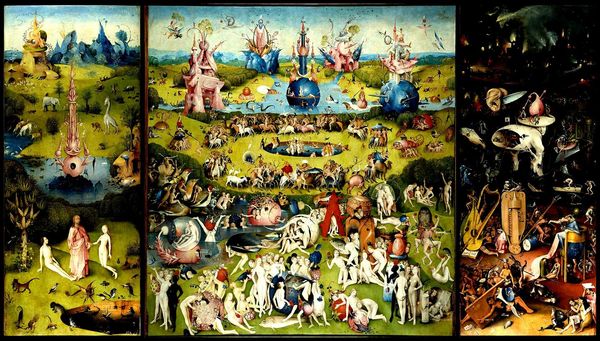

The unconscious contains all good and all evil, and is a monstrous object to behold.

On this, Jung himself has been accused of a kind of romantic fascism. Pankaj Mishra’s essay “Jordan Peterson & Fascist Mysticism” misunderstands Jung’s ideas at a fundamental level. In accusing Jung of being one of those “worshippers of the unconscious” responsible for the calamities of the twentieth century, Mishra has failed to understand the entire enterprise of Jungian psychology. Great Jungian works, including The History and Origins of Consciousness, trace the evolution of the self according to the subordination of the tyrannical unconscious to our conscious ego-morality. Jung has never advised that we sink into unconscious horror and become forces of tyrannical nature. The unconscious is the content of ‘Being’, but we are human beings and not animals precisely because concepts of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ do not exist in the animal world – they are treasures that have been introduced by the human soul, and must be organized accordingly.

That said, Jung was not infallible – his writings on women (as were Nietzsche’s) are emblematic of his time, and have aged terribly. Additionally, Jung’s earlier writings prize the “Aryan consciousness” in ways that are uncomfortably aligned with the spirit of his times, though he did cooperate with the American OSS once World War II began, and tried (and failed) to get a leading German physician to declare Hitler mad.

Jung described Hitler as “a sort of scaffolding of wood covered with a cloth, an automaton with a mask…You know you would never be able to talk to that man; because there is nobody there”. He saw Hitler purely as the projection of the German citizenry, the “unconscious of seventy-eight million Germans”.

In essence, the lunatic people are to blame for their dictator, not the single lunatic at the top. Jung, when interviewed in 1945, said of the German people: “All of them, whether consciously or unconsciously, actively or passively, have their share in the horrors.” What Jung advocated for Germany was “responsibility”, and for those who claimed their unique individual innocence, he said: “I regard the case as hopeless”. Contrary to the myopic individualism Jung is often accused of, he was a strong believer in collective guilt for the crimes of particular cultures, because they become embedded in the cultural framework which dictates the forms of the unconscious. Our unconscious approaches us in symbols, fragments, words and images, all of which are not only biological but meditated through our culture, no matter how broken or sinister it may be. If our culture is anti-Semitic, or racist, or too violent, or anything of the sort, so our unconscious may reflect it.

The Hangman

The challenge of reading Jung in an age of uncertainty is to find the enemies you recognize in the outer world dwelling inside your own heart. It is to drop culture war, group witch hunts and righteous battle against external scapegoats in the name of facing your own contradictions. Jung understood how difficult this was – he knew that our fear of the unconscious, our fear of our own innermost selves, would almost certainly prevent the sort of introspection he demanded of his patients.

This, ultimately, was why Jung believed in ‘God’ so strongly. For Jung, God was always a symbol, a stand-in for the ideal of the unified, whole self, rather than an actual entity operating in Heaven.“I put the word ‘God’ in quotes in order to indicate that we are dealing with an anthropomorphic idea (64)”, writes Jung, attaching the significance of God to the concept of a single individual who, despite being a product of circumstance and flawed, temporary cultures, is nevertheless able to attain an identification with the ideal of transcendence without looking outward to powerful leaders or seeking bulldozing impact over the world.

The answer to the unforgiving world is fidelity to oneself. Jung asks of us all: “Have I any religious experience and immediate relation to God, and hence that certainty which will keep me, as an individual, from dissolving in the crowd? (62)”. In an age of atheism, Western people have to find a new God, that is, a new organizing ideal of the highest order, which speaks to our transcendental experiences without making us scapegoating monsters. One thing is for certain – that God won’t come from the outer world. As long as your God is in the world, it can be destroyed there, and force you to reconcile its absence with even worse terror than before. God is the complete self, not the fractured madman hunting others.

Part of coming to terms with the victim of the gulag, of Auschwitz, of the lynching tree, is that even if you and I are the all-too-human murderer who has shaped history, the dead are not forgotten. The living murderers, shown their crimes, live in a state of eternal remembrance, so long as they stay honest, and recognize in themselves the dark heart of the hangman.