Jon Brooks • • 5 min read

François de La Rochefoucauld’s Short Essay on the Tyranny of Self-Love

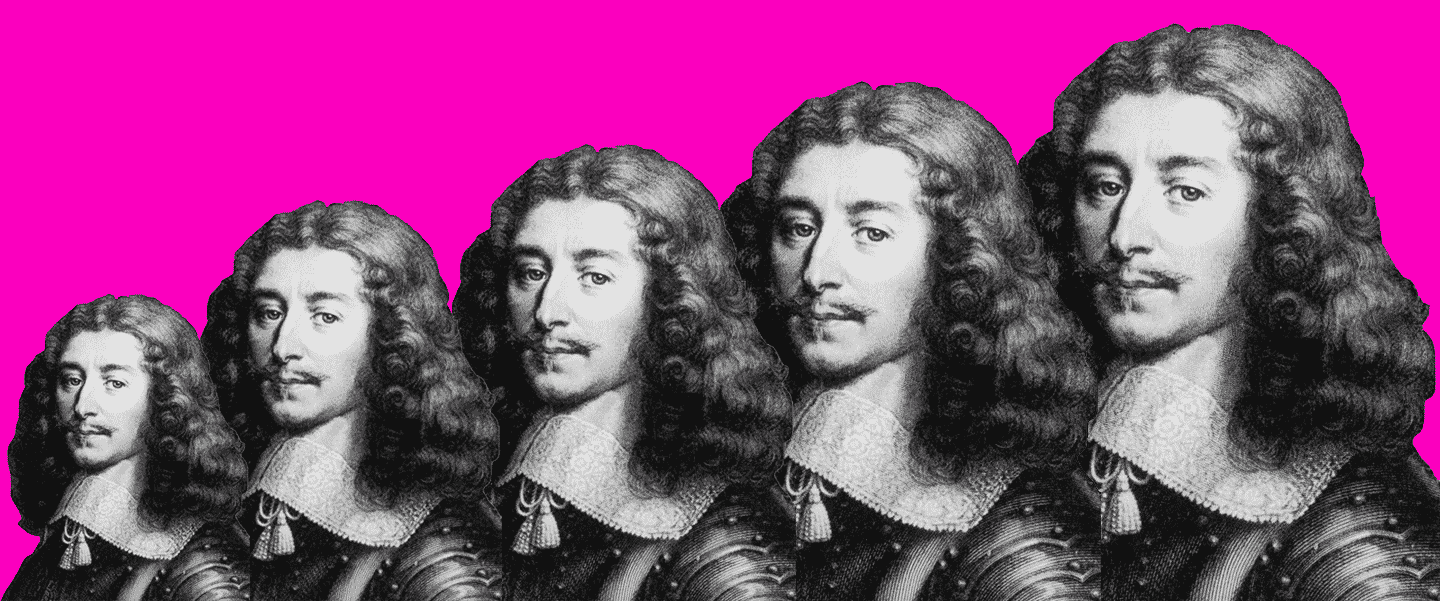

Best-selling of philosophy author Alain de Botton provides the following biography of François de La Rochefoucauld:

“The Duc de La Rochefoucauld was born in Paris in 1613, and despite his many initial advantages (wealth, connections, looks, and a very beautiful and ancient name), he had a thoroughly difficult and often miserable life. He fell in love with a couple of duchesses who didn’t treat him well; he ended up in prison after some bungled but honorable political maneuvering. He was forced into exile from his beloved Paris on four occasions. He never advanced as far as he wanted at court. He got shot in the eye during a rebellion and almost went blind. He lost most of his money, and his enemies published what they falsely purported to be his memoirs, full of insults against people whom he liked and depended on, who then turned against him and refused to believe in his innocence.”

[…]

“[He] wrote a very slim book, barely 60 pages long that can deservedly be counted as one of the true masterpieces of philosophy. The book is a compendium of acerbic melancholy observations about the human condition.”

That book is called Maxims, and it includes 641 in total. There are many repeating themes explored in La Rochefoucauld’s observations such as betrayal, flirtation, desire, and selfishness. But the trait which seems to fascinate La Rochefoucauld the most is that of self-love.

The Maxims are littered with aphorisms on self-love such as “In jealousy there is more self-love than love.” Or, “Fewer men are made cruel by natural ferocity than by self-love.” But at the end of the Penguin Classics version of the book, under the section “Maxims Withdrawn by the Author,” we can find a piece on self-love which is far closer to an essay than an aphorism.

As you read the following dissection of self-love try, try reconnect it to your own life. La Rochefoucauld described his book a “portrait of the human heart.” It is designed to illuminate the dark recesses of your shadow side with the torch of embarrassment and push you into a wiser way of being. Note how the use of “self-love” is often interchangeable with the Buddha’s use of “ego.”

La Rochefoucauld’s portrait of self-love in full:

“Self-love is love of oneself and of all things in terms of oneself; it makes men worshippers of themselves and would make them tyrants over others if fortune gave them the means. It never pauses for rest outside the self, and, like bees on flowers, only settles on outside matters in order to draw from them what suits its own requirements. Nothing is so vehement as its desires, nothing so concealed as its aims, nothing so devious as its methods; its sinuosities beggar the imagination, its transformations surpass metamorphoses, its complications go beyond those of chemistry.

No man can plumb the depths or pierce the darkness of its chasms in which, hidden from the sharpest eyes, it performs a thousand imperceptible twists and turns, and where it is often invisible even to itself and unknowingly conceives, nourishes, and brings up a vast brood of affections and hatreds. Some of these are such monstrosities that on giving them birth it either repudiates them outright or hesitates to own them. From this enveloping darkness come the ludicrous ideas it has about its own nature—the errors, ignorances, obtusenesses, and sillinesses where itself is concerned—believing, for instance, that its emotions are dead when they are merely dormant, that it has given up wanting to run just because it is resting, or that it has lost the tastes it has satiated.

But this thick darkness that hides it from itself does not prevent its seeing with perfect clarity things outside itself, just as our eyes can perceive everything else and are only blind when it comes to seeing themselves. Indeed, where its main interests and really important affairs are concerned, and the violence of its desires takes up the whole of its attention, self-love sees, feels, hears, imagines, suspects, penetrates, and guesses everything, and one is tempted to believe that its every passion has magical properties of its own. Nothing is so strong and binding as its attachments, and even under the threat of the direst calamities it struggles in vain to loosen their hold. Yet sometimes, in no time and with no effort whatever, it can do things that for years on end and with the utmost exertions it had never succeeded in doing. From all this one might reasonably conclude that its desires are kindled by itself alone rather than by the beauty or value of the things desired, which are given their price and their lustre by its taste alone, and that when it pursues things that are to its liking it is running after itself, for that is really what it likes.

It is made of all the opposites: domineering and obedient, sincere and deceitful, merciful and cruel, timid and daring. Its inclinations vary with the varying temperaments that bend its energies now towards glory, now riches, now pleasures. Self-love rings the changes on these according to our age, fortune, or experience, but whether it has several desires or only one is unimportant because it can spread its interest over several or concentrate upon one as need arises or as it pleases.

It is inconsistent, for apart from changes due to outside causes there are countless others arising from within itself: it is inconstant through sheer inconstancy or through shallowness, love, thirst for novelty, weariness, or satiety. It is capricious, and at times you can see it striving with the utmost eagerness and unbelievable toil to get things which are in no way advantageous and are even harmful, but which it pursues simply because it wants them. It is fantastical, and often concentrates all its energy upon the most frivolous occupations, finds pleasure in the most vapid, and can keep its pride intact while doing the most despicable things.

It exists at all stages of life and at all levels, finds a living everywhere, on everything or on nothing, thrives equally well on things or on their absence, even joins forces with its declared enemies and identifies itself with their tactics and, most remarkable of all, hates itself with them, plots for its own downfall and even works to bring about its own ruin: in fine, all it cares about is existing, and provided it can go on existing it is quite prepared to be its own enemy. Hence there is nothing to be surprised at if it sometimes throws in its lot with the most rigorous austerity and brazenly joins therewith for its own destruction, for the moment of its defeat on one side is that of its recovery on another. When you think it is giving up what it enjoys it is only calling a temporary halt or ringing the changes, and at the very time when it is vanquished and you think you are rid of it, back it comes, triumphant in its own undoing.

Such is the portrait of self-love, whose whole existence is one long and incessant activity. It may fittingly be likened to the sea, the ebb and flow of whose unceasing waves is a faithful picture of the turbulent succession of its thoughts and of its eternal restlessness.”

Further resources on La Rochefoucauld:

- The School of Life: ON PHILOSOPHY — La Rochefoucauld

- Maxims by François de La Rochefoucauld

Jon Brooks

Jon Brooks is a Stoicism teacher and, crucially, practitioner. His Stoic meditations have accumulated thousands of listens, and he has created his own Stoic training program for modern-day Stoics.

![Seneca’s Groundless Fears: 11 Stoic Principles for Overcoming Panic [Video]](/content/images/size/w600/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/seneca.png)